Próximo: Introdução, Acima: (dir) [Conteúdo][Índice]

GNU Guix

Esse documento descreve Guix versão 4538aa4, uma ferramenta de gerenciamento de pacotes funcional escrita para o sistema GNU.

Este manual também está disponível em inglês (veja GNU Guix Reference Manual), chinês simplificado (veja GNU Guix参考手册), francês (veja Manuel de référence de GNU Guix), alemão (veja Referenzhandbuch zu GNU Guix), espanhol (veja Manual de referencia de GNU Guix) e russo (veja Руководство GNU Guix). Se você quiser traduzi-lo para seu idioma nativo, considere participar do Weblate (veja Traduzindo o Guix).

Sumário

- 1 Introdução

- 2 Instalação

- 3 Instalação do sistema

- 3.1 Limitações

- 3.2 Considerações de Hardware

- 3.3 Instalação em um pendrive e em DVD

- 3.4 Preparando para instalação

- 3.5 Instalação gráfica guiada

- 3.6 Instalação manual

- 3.7 Após a instalação do sistema

- 3.8 Instalando Guix em uma Máquina Virtual

- 3.9 Compilando a imagem de instalação

- 3.10 Construindo a imagem de instalação para placas ARM

- 4 Começando

- 5 Gerenciamento de pacote

- 6 Canais

- 6.1 Especificando canais adicionais

- 6.2 Usando um canal Guix personalizado

- 6.3 Replicando Guix

- 6.4 Customizing the System-Wide Guix

- 6.5 Autenticação de canal

- 6.6 Canais com substitutos

- 6.7 Criando um canal

- 6.8 Módulos de pacote em um subdiretório

- 6.9 Declarando dependências de canal

- 6.10 Especificando autorizações de canal

- 6.11 URL principal

- 6.12 Escrevendo notícias do canal

- 7 Desenvolvimento

- 8 Interface de programação

- 8.1 Módulos de pacote

- 8.2 Definindo pacotes

- 8.3 Definindo variantes de pacote

- 8.4 Escrevendo manifestos

- 8.5 Sistemas de compilação

- 8.6 Fases de construção

- 8.7 Construir utilitários

- 8.8 Caminhos de pesquisa

- 8.9 O armazém

- 8.10 Derivações

- 8.11 A mônada do armazém

- 8.12 Expressões-G

- 8.13 Invocando

guix repl - 8.14 Usando Guix interativamente

- 9 Utilitários

- 9.1 Invocando

guix build - 9.2 Invocando

guix edit - 9.3 Invocando

guix download - 9.4 Invocando

guix hash - 9.5 Invoking

guix import - 9.6 Invocando

guix refresh - 9.7 Invoking

guix style - 9.8 Invocando

guix lint - 9.9 Invocando

guix size - 9.10 Invocando

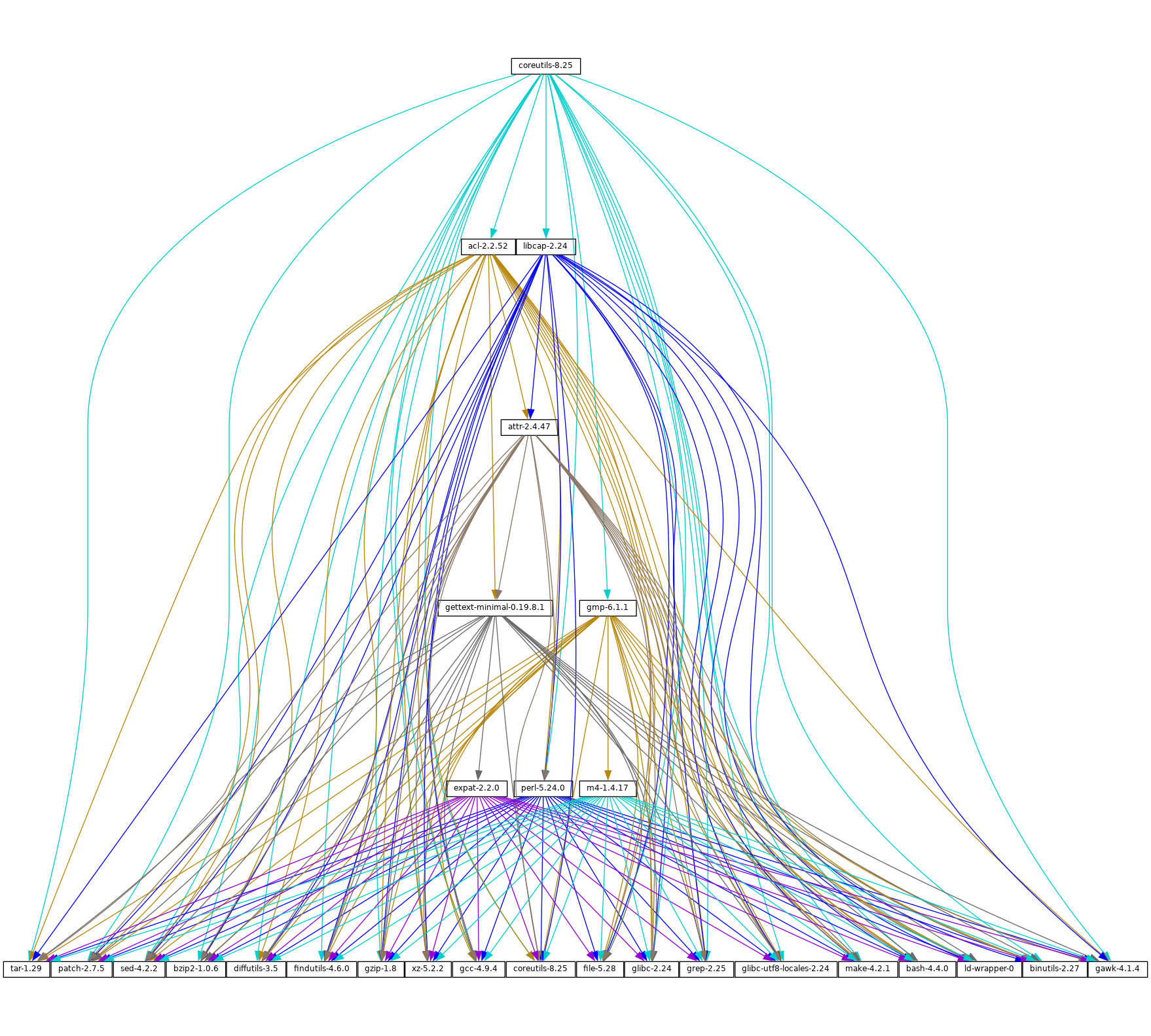

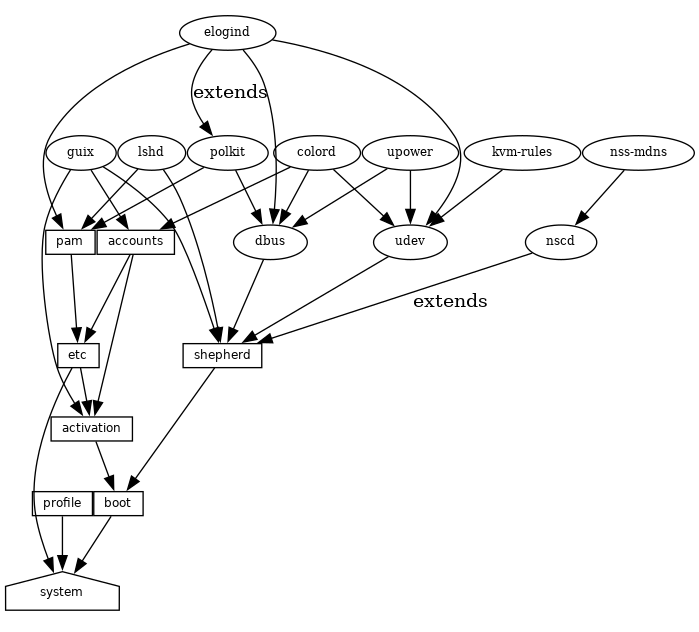

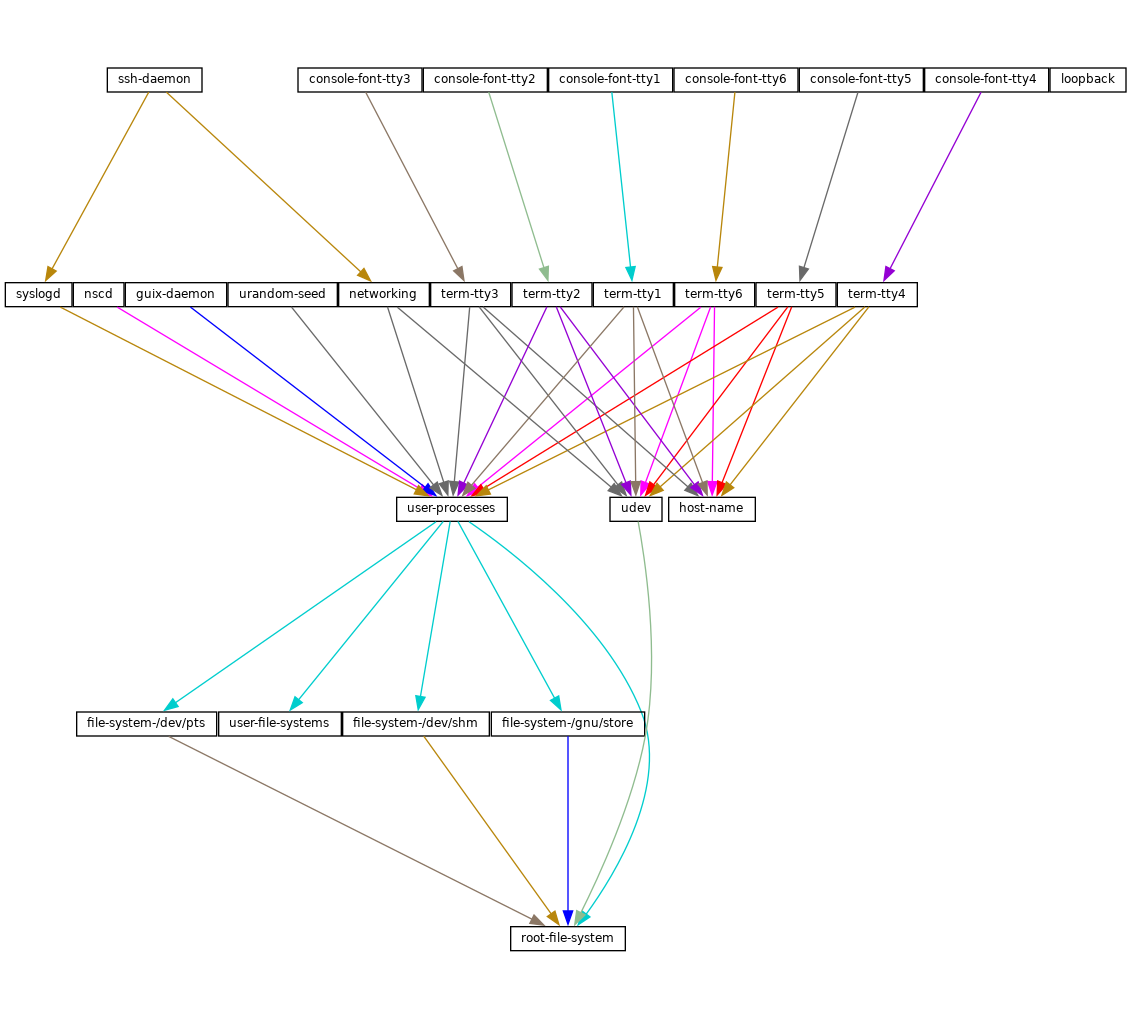

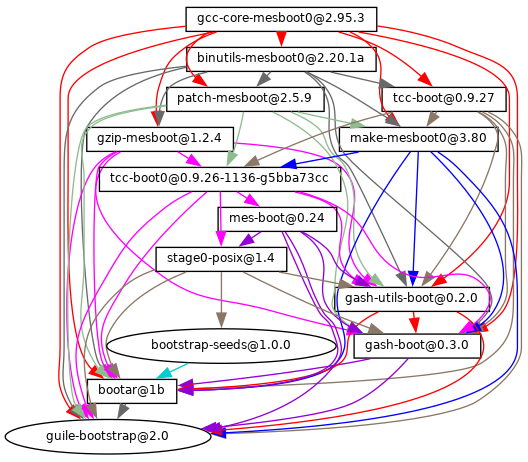

guix graph - 9.11 Invocando

guix publish - 9.12 Invocando

guix challenge - 9.13 Invocando

guix copy - 9.14 Invocando

guix container - 9.15 Invocando

guix weather - 9.16 Invocando

guix processes

- 9.1 Invocando

- 10 Arquiteturas Estrangeiras

- 11 Configuração do sistema

- 11.1 Começando

- 11.2 Usando o sistema de configuração

- 11.3

operating-systemReference - 11.4 Sistemas de arquivos

- 11.5 Dispositivos mapeados

- 11.6 Espaço de troca (swap)

- 11.7 Contas de usuário

- 11.8 Disposição do teclado

- 11.9 Localidades

- 11.10 Serviços

- 11.10.1 Serviços básicos

- 11.10.2 Execução de trabalho agendado

- 11.10.3 Rotação de log

- 11.10.4 Networking Setup

- 11.10.5 Serviços de Rede

- 11.10.6 Atualizações sem supervisão

- 11.10.7 X Window

- 11.10.8 Serviços de impressão

- 11.10.9 Serviços de desktop

- 11.10.10 Serviços de som

- 11.10.11 File Search Services

- 11.10.12 Serviços de bancos de dados

- 11.10.13 Serviços de correio

- 11.10.14 Serviços de mensageria

- 11.10.15 Serviços de telefonia

- 11.10.16 Serviços de compartilhamento de arquivos

- 11.10.17 Serviços de monitoramento

- 11.10.18 Serviços Kerberos

- 11.10.19 Serviços LDAP

- 11.10.20 Serviços web

- 11.10.21 Serviços de certificado

- 11.10.22 Serviços DNS

- 11.10.23 VNC Services

- 11.10.24 Serviços VPN

- 11.10.25 Sistema de arquivos de rede

- 11.10.26 Samba Services

- 11.10.27 Integração Contínua

- 11.10.28 Serviços de gerenciamento de energia

- 11.10.29 Serviços de áudio

- 11.10.30 Serviços de virtualização

- 11.10.31 Serviços de controlando versão

- 11.10.32 Serviços de jogos

- 11.10.33 Serviço de montagem PAM

- 11.10.34 Serviços Guix

- 11.10.35 Serviços Linux

- 11.10.36 Serviços Hurd

- 11.10.37 Serviços diversos

- 11.11 Privileged Programs

- 11.12 Certificados X.509

- 11.13 Name Service Switch

- 11.14 Disco de RAM inicial

- 11.15 Configuração do carregador de inicialização

- 11.16 Invoking

guix system - 11.17 Invoking

guix deploy - 11.18 Usando o Guix em uma Máquina Virtual

- 11.19 Definindo serviços

- 12 Dicas para solução de problemas do sistema

- 13 Home Configuration

- 13.1 Declarando o ambiente pessoal

- 13.2 Configurando o "Shell"

- 13.3 Serviços pessoais

- 13.3.1 Serviços essenciais pessoais

- 13.3.2 Shells

- 13.3.3 Execução de trabalho agendado pessoal

- 13.3.4 Power Management Home Services

- 13.3.5 Managing User Daemons

- 13.3.6 Secure Shell

- 13.3.7 GNU Privacy Guard

- 13.3.8 Desktop Home Services

- 13.3.9 Guix Home Services

- 13.3.10 Fonts Home Services

- 13.3.11 Sound Home Services

- 13.3.12 Mail Home Services

- 13.3.13 Messaging Home Services

- 13.3.14 Media Home Services

- 13.3.15 Gerenciador de janelas Sway

- 13.3.16 Networking Home Services

- 13.3.17 Miscellaneous Home Services

- 13.4 Invoking

guix home

- 14 Documentação

- 15 Plataformas

- 16 Criando imagens do sistema

- 17 Instalando arquivos de depuração

- 18 Usando TeX e LaTeX

- 19 Atualizações de segurança

- 20 Inicializando

- 21 Portando para uma nova plataforma

- 22 Contribuindo

- 22.1 Requisitos

- 22.2 Compilando do git

- 22.3 Executando o conjunto de testes

- 22.4 Executando guix antes dele ser instalado

- 22.5 A configuração perfeita

- 22.6 Configurações alternativas

- 22.7 Estrutura da árvore de origem

- 22.8 Diretrizes de empacotamento

- 22.8.1 Liberdade de software

- 22.8.2 Nomeando um pacote

- 22.8.3 Números de versão

- 22.8.4 Sinopses e descrições

- 22.8.5 Snippets versus Phases

- 22.8.6 Dependências do módulo cíclico

- 22.8.7 Pacotes Emacs

- 22.8.8 Módulos Python

- 22.8.9 Módulos Perl

- 22.8.10 Pacotes Java

- 22.8.11 Rust Crates

- 22.8.12 Pacotes Elm

- 22.8.13 Fontes

- 22.9 Estilo de código

- 22.10 Enviando patches

- 22.11 Rastreando Bugs e Mudanças

- 22.12 Equipes

- 22.13 Tomando decisões

- 22.14 Confirmar acesso

- 22.15 Revendo o trabalho de outros

- 22.16 Atualizando o pacote Guix

- 22.17 Política de depreciação

- 22.18 Escrevendo documentação

- 22.19 Traduzindo o Guix

- 22.20 Contributing to Guix’s Infrastructure

- 23 Agradecimentos

- Apêndice A Licença de Documentação Livre GNU

- Índice de conceitos

- Índice de programação

Próximo: Instalação, Anterior: GNU Guix, Acima: GNU Guix [Conteúdo][Índice]

1 Introdução

GNU Guix1 é uma ferramenta de gerenciamento de pacotes e distribuição do sistema GNU. O Guix facilita a instalação, a atualização ou a remoção de pacotes de software, a reversão para um conjunto de pacotes anterior, a compilação de pacotes a partir do código-fonte e geralmente ajuda na criação e manutenção de ambientes de software.

Você pode instalar o GNU Guix sobre um sistema GNU/Linux existente, onde ele complementa as ferramentas disponíveis sem interferência (veja Instalação) ou você pode usá-lo como uma distribuição de sistema operacional independente, Guix System2. Veja Distribuição GNU.

Próximo: Distribuição GNU, Acima: Introdução [Conteúdo][Índice]

1.1 Gerenciando software do jeito do Guix

O Guix fornece uma interface de gerenciamento de pacotes de linha de comando (veja Gerenciamento de pacote), ferramentas para ajudar no desenvolvimento de software (veja Desenvolvimento), utilitários de linha de comando para uso mais avançado (veja Utilitários), bem como interfaces de programação Scheme (veja Interface de programação). O build daemon é responsável por compilar pacotes em nome dos usuários (veja Configurando o daemon) e por baixar binários pré-compilados de fontes autorizados (veja Substitutos).

Guix inclui definições de pacotes para muitos pacotes GNU e não-GNU, todos os quais respeitam a liberdade de computação do usuário. É extensível: os usuários podem escrever suas próprias definições de pacotes (veja Definindo pacotes) e disponibilizá-los como módulos de pacotes independentes (veja Módulos de pacote). Também é personalizável: os usuários podem derivar definições de pacotes especializados das existentes, incluindo da linha de comando (veja Opções de transformação de pacote).

Nos bastidores, a Guix implementa a disciplina gerenciamento de pacotes funcional pioneira da Nix (veja Agradecimentos). No Guix, o processo de compilação e instalação de pacotes é visto como uma função, no sentido matemático. Essa função recebe entradas, como scripts de compilação, um compilador e bibliotecas, e retorna um pacote instalado. Como uma função pura, seu resultado depende apenas de suas entradas – por exemplo, não pode fazer referência a um software ou scripts que não foram explicitamente passados como entradas. Uma função de compilação sempre produz o mesmo resultado ao passar por um determinado conjunto de entradas. Não pode alterar o ambiente do sistema em execução de qualquer forma; por exemplo, ele não pode criar, modificar ou excluir arquivos fora de seus diretórios de compilação e instalação. Isto é conseguido através da execução de processos de compilação em ambientes isolados (ou containers), onde somente suas entradas explícitas são visíveis.

O resultado das funções de compilação do pacote é mantido (cached) no sistema de arquivos, em um diretório especial chamado armazém (veja O armazém). Cada pacote é instalado em um diretório próprio no armazém – por padrão, em /gnu/store. O nome do diretório contém um hash de todas as entradas usadas para compilar esse pacote; Assim, a alteração uma entrada gera um nome de diretório diferente.

Essa abordagem é a fundação para os principais recursos do Guix: suporte para atualização transacional de pacotes e reversão, instalação por usuário e coleta de lixo de pacotes (veja Recursos).

Anterior: Gerenciando software do jeito do Guix, Acima: Introdução [Conteúdo][Índice]

1.2 Distribuição GNU

O Guix vem com uma distribuição do sistema GNU que consiste inteiramente de software livre3. A distribuição pode ser instalada por conta própria (veja Instalação do sistema), mas também é possível instalar o Guix como um gerenciador de pacotes em cima de um sistema GNU/Linux instalado (veja Instalação). Quando precisamos distinguir entre os dois, nos referimos à distribuição independente como Guix System.

A distribuição fornece pacotes GNU principais, como GNU libc, GCC e

Binutils, além de muitos aplicativos GNU e não GNU. A lista completa de

pacotes disponíveis pode ser acessada

online ou executando

guix package (veja Invocando guix package):

guix package --list-available

Nosso objetivo é fornecer uma distribuição prática e 100% de software livre, baseada em Linux e outras variantes do GNU, com foco na promoção e forte integração de componentes do GNU e ênfase em programas e ferramentas que ajudam os usuários a exercer essa liberdade.

Os pacotes estão atualmente disponíveis nas seguintes plataformas:

x86_64-linuxArquitetura Intel/AMD

x86_64, kernel Linux-Libre.i686-linuxArquitetura Intel de 32 bits (IA32), kernel Linux-Libre.

armhf-linuxArquitetura ARMv7-A com hard float, Thumb-2 e NEON, usando a interface binária de aplicativos EABI hard-float (ABI) e o kernel Linux-Libre.

aarch64-linuxProcessadores ARMv8-A little-endian de 64 bits, kernel Linux-Libre.

i586-gnuGNU/Hurd sobre a arquitetura Intel de 32 bits (IA32).

Esta configuração é experimental e está em desenvolvimento. A maneira mais fácil de você tentar é configurando uma instância de

hurd-vm-service-typena sua máquina GNU/Linux (vejahurd-vm-service-type). Veja Contribuindo, sobre como ajudar!x86_64-gnuGNU/Hurd on the

x86_64Intel/AMD 64-bit architecture.This configuration is even more experimental and under heavy upstream development.

mips64el-linux (sem suporte)processadores little-endian MIPS de 64 bits, especificamente a série Loongson, n32 ABI e kernel Linux-Libre. Esta configuração não é mais totalmente suportada; em particular, não há trabalho em andamento para garantir que esta arquitetura ainda funcione. Caso alguém decida que deseja reviver esta arquitetura, o código ainda estará disponível.

powerpc-linux (sem suporte)processadores PowerPC big-endian de 32 bits, especificamente o PowerPC G4 com suporte AltiVec e kernel Linux-Libre. Esta configuração não é totalmente suportada e não há trabalho em andamento para garantir que esta arquitetura funcione.

powerpc64le-linuxprocessadores little-endian 64 bits Power ISA, kernel Linux-Libre. Isso inclui sistemas POWER9 como o placa-mãe RYF Talos II. Esta plataforma está disponível como uma "prévia de tecnologia": embora seja suportada, substitutos ainda não estão disponíveis na fazenda de construção (veja Substitutos), e alguns pacotes podem falhar na construção (veja Rastreando Bugs e Mudanças). Dito isso, a comunidade Guix está trabalhando ativamente para melhorar esse suporte, e agora é um ótimo momento para experimentá-lo e se envolver!

riscv64-linuxprocessadores little-endian RISC-V de 64 bits, especificamente RV64GC, e kernel Linux-Libre. Esta plataforma está disponível como uma "prévia de tecnologia": embora seja suportada, substitutos ainda não estão disponíveis na build farm (veja Substitutos), e alguns pacotes podem falhar na compilação (veja Rastreando Bugs e Mudanças). Dito isto, a comunidade Guix está trabalhando ativamente para melhorar este suporte, e agora é um ótimo momento para experimentá-lo e se envolver!

Com o Guix System, você declara todos os aspectos da configuração do sistema operacional, e o Guix cuida de instanciar a configuração de maneira transacional, reproduzível e sem estado (veja Configuração do sistema). O Guix System usa o kernel Linux-libre, o sistema de inicialização Shepherd (veja Introduction em The GNU Shepherd Manual), os conhecidos utilitários do GNU e cadeia de ferramentas, bem como o ambiente gráfico ou os serviços de sistema do sua escolha.

Guix System is available on all the above platforms except

mips64el-linux, powerpc-linux, powerpc64le-linux and

riscv64-linux.

Para obter informações sobre como portar para outras arquiteturas ou kernels, veja Portando para uma nova plataforma.

A construção desta distribuição é um esforço cooperativo e você está convidado a participar! Veja Contribuindo, para obter informações sobre como você pode ajudar.

Próximo: Instalação do sistema, Anterior: Introdução, Acima: GNU Guix [Conteúdo][Índice]

2 Instalação

Você pode instalar a ferramenta de gerenciamento de pacotes Guix sobre um sistema GNU/Linux ou GNU/Hurd existente4, conhecido como distro estrangeiro. Se, em vez disso, você quiser instalar a distribuição completa e autônoma do sistema GNU, Guix System, veja Instalação do sistema. Esta seção se preocupa apenas com a instalação do Guix em uma distro estrangeira.

Importante: Esta seção se aplica somente a sistemas sem Guix. Segui-la para instalações Guix existentes sobrescreverá arquivos importantes do sistema.

Quando instalado sobre uma distro alheia. GNU Guix complementa as ferramentas disponíveis sem interferência. Seus dados residem exclusivamente em dois diretórios, geralmente /gnu/store e /var/guix; outros arquivos no seu sistema, como /etc, são deixados intactos.

Uma vez instalado, o Guix pode ser atualizado executando guix pull

(veja Invocando guix pull).

- Instalação de binários

- Configurando o daemon

- Invocando

guix-daemon - Configuração de aplicativo

- Atualizando o Guix

Próximo: Configurando o daemon, Acima: Instalação [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.1 Instalação de binários

This section describes how to install Guix from a self-contained tarball providing binaries for Guix and for all its dependencies. This is often quicker than installing from source, described later (veja Compilando do git).

Importante: Esta seção se aplica somente a sistemas sem Guix. Segui-la para instalações Guix existentes sobrescreverá arquivos importantes do sistema.

Algumas distribuições GNU/Linux, como Debian, Ubuntu e openSUSE fornecem Guix por meio de seus próprios gerenciadores de pacotes. A versão do Guix pode ser mais antiga que 4538aa4, mas você pode atualizá-la depois executando ‘guix pull’.

Aconselhamos os administradores de sistema que instalam o Guix, tanto a

partir do script de instalação quanto por meio do gerenciador de pacotes

nativo de sua distribuição estrangeira, a também ler e seguir regularmente

os avisos de segurança, conforme mostrado pelo guix pull.

Para Debian ou derivados como Ubuntu ou Trisquel, chame:

sudo apt install guix

Da mesma forma, no openSUSE:

sudo zypper install guix

Se você estiver executando o Parabola, depois de habilitar o repositório pcr (Parabola Community Repo), você pode instalar o Guix com:

sudo pacman -S guix

O projeto Guix também fornece um script de shell, guix-install.sh, que automatiza o processo de instalação binária sem o uso de um gerenciador de pacotes de distro estrangeiro5. O uso de guix-install.sh requer Bash, GnuPG, GNU tar, wget e Xz.

The script guides you through the following:

- Baixando e extraindo o tarball binário

- Setting up the build daemon

- Disponibilizando o comando ‘guix’ para usuários não root

- Configuring substitute servers

Como root, execute:

# cd /tmp # wget https://git.savannah.gnu.org/cgit/guix.git/plain/etc/guix-install.sh # chmod +x guix-install.sh # ./guix-install.sh

O script para instalar o Guix também está empacotado no Parabola (no repositório pcr). Você pode instalá-lo e executá-lo com:

sudo pacman -S guix-installer sudo guix-install.sh

Nota: Por padrão, guix-install.sh configurará o Guix para baixar binários de pacotes pré-construídos, chamados substitutes (veja Substitutos), das fazendas de construção do projeto. Se você escolher não permitir isso, o Guix construirá tudo a partir da fonte, tornando cada instalação e atualização muito cara. Veja Confiança em binários para uma discussão sobre por que você pode querer construir pacotes a partir da fonte.

Para usar substitutos de

bordeaux.guix.gnu.org,ci.guix.gnu.orgou um espelho, você deve autorizá-los. Por exemplo,# guix archive --authorize < \ ~root/.config/guix/current/share/guix/bordeaux.guix.gnu.org.pub # guix archive --authorize < \ ~root/.config/guix/current/share/guix/ci.guix.gnu.org.pub

Quando terminar de instalar o Guix, veja Configuração de aplicativo para configurações extras que você pode precisar e Começando para seus primeiros passos!

Nota: O tarball da instalação binária pode ser (re)produzido e verificado simplesmente executando o seguinte comando na árvore de código-fonte do Guix:

make guix-binary.sistema.tar.xz... que, por sua vez, executa:

guix pack -s sistema --localstatedir \ --profile-name=current-guix guixVeja Invocando

guix pack, para mais informações sobre essa ferramenta útil.

Caso você queira desinstalar o Guix, execute o mesmo script com o sinalizador --uninstall:

./guix-install.sh --uninstall

Com --uninstall, o script exclui irreversivelmente todos os arquivos Guix, configuração e serviços.

Próximo: Invocando guix-daemon, Anterior: Instalação de binários, Acima: Instalação [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.2 Configurando o daemon

Durante a instalação, o build daemon que deve estar em execução para

usar o Guix já foi configurado e você pode executar comandos guix

no seu programa de terminal, veja Começando:

guix build hello

Se isso ocorrer sem erros, sinta-se à vontade para pular esta seção. Você deve continuar com a seção seguinte, Configuração de aplicativo.

No entanto, agora seria um bom momento para substituir versões

desatualizadas do daemon, ajustá-lo, executar compilações em outras máquinas

(veja Usando o recurso de descarregamento) ou iniciá-lo manualmente em ambientes

especiais como “chroots” (veja Acessando um sistema existente via chroot) ou

WSL (não necessário para imagens WSL criadas com Guix, veja wsl2-image-type). Se você quiser saber mais ou otimizar seu sistema,

vale a pena ler esta seção.

Operações como compilar um pacote ou executar o coletor de lixo são todas

executadas por um processo especializado, o build daemon, em nome dos

clientes. Apenas o daemon pode acessar o armazém e seu banco de dados

associado. Assim, qualquer operação que manipule o armazém passa pelo

daemon. Por exemplo, ferramentas de linha de comando como guix

package e guix build se comunicam com o daemon (via chamadas

de procedimento remoto) para instruir o que fazer.

As seções a seguir explicam como preparar o ambiente do daemon de compilação. Veja Substitutos para informações sobre como permitir que o daemon baixe binários pré-compilados.

Próximo: Usando o recurso de descarregamento, Acima: Configurando o daemon [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.2.1 Configuração do ambiente de compilação

Em uma configuração multiusuário padrão, o Guix e seu daemon – o programa

guix-daemon – são instalados pelo administrador do sistema;

/gnu/store é de propriedade de root e guix-daemon é

executado como root. Usuários desprivilegiados podem usar ferramentas

Guix para criar pacotes ou acessar o armazém, e o daemon fará isso em seu

nome, garantindo que o armazém seja mantido em um estado consistente e

permitindo que pacotes construídos sejam compartilhados entre os usuários.

Quando guix-daemon é executado como root, você pode não

querer que os próprios processos de compilação de pacotes também sejam

executados como root, por razões óbvias de segurança. Para evitar

isso, um conjunto especial de usuários de compilação deve ser criado

para uso pelos processos de construção iniciados pelo daemon. Esses usuários

de compilação não precisam ter um shell e um diretório pessoal: eles serão

usados apenas quando o daemon der um privilégio root nos processos de

compilação. Ter vários desses usuários permite que o daemon ative processos

de compilação distintos sob UIDs separados, o que garante que eles não

interfiram uns com os outros - um recurso essencial, pois as compilações são

consideradas funções puras (veja Introdução).

Em um sistema GNU/Linux, um conjunto de usuários de construção pode ser

criado assim (usando a sintaxe Bash e os comandos shadow):

# groupadd --system guixbuild

# for i in $(seq -w 1 10);

do

useradd -g guixbuild -G guixbuild \

-d /var/empty -s $(which nologin) \

-c "Guix build user $i" --system \

guixbuilder$i;

done

O número de usuários de compilação determina quantos trabalhos de compilação

podem ser executados em paralelo, conforme especificado pela opção

--max-jobs (veja --max-jobs). Para usar guix system vm e comandos

relacionados, você pode precisar adicionar os usuários de compilação ao

grupo kvm para que eles possam acessar /dev/kvm, usando

-G guixbuild,kvm em vez de -G guixbuild (veja Invoking guix system).

The guix-daemon program may then be run as root with the

following command6:

# guix-daemon --build-users-group=guixbuild

Dessa forma, o daemon inicia os processos de compilação em um chroot, sob um

dos usuários guixbuilder. No GNU/Linux, por padrão, o ambiente chroot

contém nada além de:

- um diretório

/devmínimo, criado principalmente independentemente do/devdo hospedeiro7; - o diretório

/proc; mostra apenas os processos do contêiner desde que um espaço de nome PID separado é usado; - /etc/passwd com uma entrada para o usuário atual e uma entrada para o usuário nobody;

- /etc/group com uma entrada para o grupo de usuários;

- /etc/hosts com uma entrada que mapeia

localhostpara127.0.0.1; - um diretório /tmp com permissão de escrita.

O chroot não contém um diretório /home, e a variável de ambiente

HOME é definida como o inexistente /homeless-shelter. Isso

ajuda a destacar usos inapropriados de HOME nos scripts de construção

de pacotes.

Tudo isso geralmente é suficiente para garantir que os detalhes do ambiente não influenciem os processos de construção. Em alguns casos excepcionais em que mais controle é necessário — normalmente sobre a data, kernel ou CPU — você pode recorrer a uma máquina de construção virtual (veja máquinas de construção virtual).

Você pode influenciar o diretório onde o daemon armazena árvores de build

via a variável de ambiente TMPDIR. No entanto, a árvore de build

dentro do chroot é sempre chamada /tmp/guix-build-name.drv-0,

onde name é o nome da derivação—por exemplo,

coreutils-8.24. Dessa forma, o valor de TMPDIR não vaza dentro

de ambientes de build, o que evita discrepâncias em casos em que os

processos de build capturam o nome de sua árvore de build.

O daemon também respeita as variáveis de ambiente http_proxy e

https_proxy para downloads HTTP e HTTPS que ele realiza, seja para

derivações de saída fixa (veja Derivações) ou para substitutos

(veja Substitutos).

Se você estiver instalando o Guix como um usuário sem privilégios, ainda é

possível executar guix-daemon desde que você passe

--disable-chroot. No entanto, os processos de construção não serão

isolados uns dos outros, e nem do resto do sistema. Assim, os processos de

construção podem interferir uns nos outros, e podem acessar programas,

bibliotecas e outros arquivos disponíveis no sistema — tornando muito mais

difícil visualizá-los como funções puras.

Próximo: Suporte a SELinux, Anterior: Configuração do ambiente de compilação, Acima: Configurando o daemon [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.2.2 Usando o recurso de descarregamento

Quando desejado, o daemon de compilação pode offload compilações de

derivação para outras máquinas executando Guix, usando o offload

build hook8. Quando esse recurso é habilitado, uma lista de máquinas de

compilação especificadas pelo usuário é lida de

/etc/guix/machines.scm; toda vez que uma compilação é solicitada, por

exemplo via guix build, o daemon tenta descarregá-la para uma das

máquinas que satisfazem as restrições da derivação, em particular seus tipos

de sistema — por exemplo, x86_64-linux. Uma única máquina pode ter

vários tipos de sistema, seja porque sua arquitetura o suporta nativamente,

via emulação (veja Transparent Emulation with

QEMU), ou ambos. Os pré-requisitos ausentes para a compilação são copiados

por SSH para a máquina de destino, que então prossegue com a compilação; em

caso de sucesso, a(s) saída(s) da compilação são copiadas de volta para a

máquina inicial. O recurso de offload vem com um agendador básico que tenta

selecionar a melhor máquina. A melhor máquina é escolhida entre as máquinas

disponíveis com base em critérios como:

- A disponibilidade de um slot de build. Uma máquina de build pode ter tantos

slots de build (conexões) quanto o valor do campo

parallel-buildsdo seu objetobuild-machine. - Sua velocidade relativa, conforme definida pelo campo

speeddo seu objetobuild-machine. - Sua carga. A carga normalizada da máquina deve ser menor que um valor

limite, configurável por meio do campo

overload-thresholdde seu objetobuild-machine. - Disponibilidade de espaço em disco. Mais de 100 MiB devem estar disponíveis.

O arquivo /etc/guix/machines.scm geralmente se parece com isso:

(list (build-machine

(name "eightysix.example.org")

(systems (list "x86_64-linux" "i686-linux"))

(host-key "ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3Nza…")

(user "bob")

(speed 2.)) ;incredibly fast!

(build-machine

(name "armeight.example.org")

(systems (list "aarch64-linux"))

(host-key "ssh-rsa AAAAB3Nza…")

(user "alice")

;; Lembre-se de que 'guix offload' é gerado por

;; 'guix-daemon' como root.

(private-key "/root/.ssh/identity-for-guix")))

No exemplo acima, especificamos uma lista de duas máquinas de compilação,

uma para as arquiteturas x86_64 e i686 e uma para a

arquitetura aarch64.

De fato, esse arquivo é – não surpreendentemente! – um arquivo de Scheme

que é avaliado quando o hook offload é iniciado. Seu valor de retorno

deve ser uma lista de objetos de build-machine. Embora este exemplo

mostre uma lista fixa de máquinas de compilação, pode-se imaginar, digamos,

usando DNS-SD para retornar uma lista de possíveis máquinas de compilação

descobertas na rede local (veja Guile-Avahi em Using Avahi in Guile Scheme Programs). O tipo de dados de

build-machine está detalhado abaixo.

- Tipo de dados: build-machine

Esse tipo de dados representa máquinas de compilação nas quais o daemon pode descarregar compilações. Os campos importantes são:

nameO nome de host da máquina remota.

systemsO sistema digita os tipos que a máquina remota suporta, por exemplo,

(list "x86_64-linux" "i686-linux").userThe user account on the remote machine to use when connecting over SSH. Note that the SSH key pair must not be passphrase-protected, to allow non-interactive logins.

host-keyEssa deve ser a SSH chave pública do host da máquina no formato OpenSSH. Isso é usado para autenticar a máquina quando nos conectamos a ela. É uma string longa que se parece com isso:

ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC…mde+UhL hint@example.org

Se a máquina estiver executando o daemon OpenSSH,

sshd, a chave do host poderá ser encontrada em um arquivo como /etc/ssh/ssh_host_ed25519_key.pub.Se a máquina estiver executando o daemon SSH do GNU lsh,

lshd, a chave do host estará em /etc/lsh/host-key.pub ou em um arquivo semelhante. Ele pode ser convertido para o formato OpenSSH usando olsh-export-key(veja Converting keys em LSH Manual):$ lsh-export-key --openssh < /etc/lsh/host-key.pub ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAAEOp8FoQAAAQEAs1eB46LV…

Vários campos opcionais podem ser especificados:

port(padrão:22)O número da porta para o servidor SSH na máquina.

private-key(padrão: ~root/.ssh/id_rsa)O arquivo de chave privada SSH a ser usado ao conectar-se à máquina, no formato OpenSSH. Esta chave não deve ser protegida com uma senha.

Observe que o valor padrão é a chave privada da usuário root. Verifique se ele existe se você usar o padrão.

compression(padrão:"zlib@openssh.com,zlib")compression-level(padrão:3)Os métodos de compactação no nível SSH e o nível de compactação solicitado.

Observe que o descarregamento depende da compactação SSH para reduzir o uso da largura de banda ao transferir arquivos de e para máquinas de compilação.

daemon-socket(padrão:"/var/guix/daemon-socket/socket")O nome do arquivo do soquete do domínio Unix

guix-daemonestá escutando nessa máquina.overload-threshold(default:0.8)O limite de carga acima do qual uma máquina de offload potencial é desconsiderada pelo agendador de offload. O valor traduz aproximadamente o uso total do processador da máquina de build, variando de 0,0 (0%) a 1,0 (100%). Ele também pode ser desabilitado definindo

overload-thresholdpara#f.parallel-builds(padrão:1)O número de compilações que podem ser executadas paralelamente na máquina.

speed(padrão:1.0)Um “fator de velocidade relativo”. O agendador de descarregamento tenderá a preferir máquinas com um fator de velocidade mais alto.

features(padrão:'())Uma lista de strgins que denotam recursos específicos suportados pela máquina. Um exemplo é

"kvm"para máquinas que possuem os módulos KVM Linux e o suporte de hardware correspondente. As derivações podem solicitar recursos pelo nome e serão agendadas nas máquinas de compilação correspondentes.

Nota: No Guix System, em vez de gerenciar /etc/guix/machines.scm de forma independente, você pode escolher especificar máquinas de compilação diretamente na declaração

operating-system, no campobuild-machinesdeguix-configuration. Veja campobuild-machinesdeguix-configuration.

O comando guix deve estar no caminho de pesquisa nas máquinas de

compilação. Você pode verificar se este é o caso executando:

ssh build-machine guix repl --version

Há uma última coisa a fazer quando o machines.scm está em vigor. Como

explicado acima, ao descarregar, os arquivos são transferidos entre os

armazéns das máquinas. Para que isso funcione, primeiro você precisa gerar

um par de chaves em cada máquina para permitir que o daemon exporte arquivos

assinados de arquivos do armazém (veja Invocando guix archive):

# guix archive --generate-key

Nota: Este par de chaves não está relacionado ao par de chaves SSH mencionado anteriormente na descrição do tipo de dados

build-machine.

Cada máquina de construção deve autorizar a chave da máquina principal para que ela aceite itens do armazém que recebe do mestre:

# guix archive --authorize < master-public-key.txt

Da mesma forma, a máquina principal deve autorizar a chave de cada máquina de compilação.

Todo esse barulho com as chaves está aqui para expressar relações de confiança mútua de pares entre a máquina mestre e as de compilação. Concretamente, quando o mestre recebe arquivos de uma máquina de compilação (e vice-versa), seu daemon de compilação pode garantir que eles sejam genuínos, não tenham sido violados e que sejam assinados por uma chave autorizada.

Para testar se sua configuração está operacional, execute este comando no nó principal:

# guix offload test

Isso tentará se conectar a cada uma das máquinas de compilação especificadas em /etc/guix/machines.scm, certificar-se de que o Guix esteja disponível em cada máquina, tentará exportar para a máquina e importar dela e relatará qualquer erro no processo.

Se você quiser testar um arquivo de máquina diferente, basta especificá-lo na linha de comando:

# guix offload test machines-qualif.scm

Por fim, você pode testar o subconjunto das máquinas cujo nome corresponde a uma expressão regular como esta:

# guix offload test machines.scm '\.gnu\.org$'

Para exibir o carregamento atual de todos os hosts de compilação, execute este comando no nó principal:

# guix offload status

Anterior: Usando o recurso de descarregamento, Acima: Configurando o daemon [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.2.3 Suporte a SELinux

O Guix inclui um arquivo de políticas do SELinux em etc/guix-daemon.cil que pode ser instalado em um sistema em que o SELinux está ativado, para rotular os arquivos do Guix e especificar o comportamento esperado do daemon. Como o Guix System não fornece uma política básica do SELinux, a política do daemon não pode ser usada no Guix System.

2.2.3.1 Instalando a política do SELinux

Nota: O script de instalação binária

guix-install.shse oferece para executar as etapas abaixo para você (veja Instalação de binários).

Para instalar a política, execute esse comando como root:

semodule -i /var/guix/profiles/per-user/root/current-guix/share/selinux/guix-daemon.cil

Então, como root, renomeie o sistema de arquivos, possivelmente depois de torná-lo gravável:

mount -o remount,rw /gnu/store restorecon -R /gnu /var/guix

Neste ponto, você pode iniciar ou reiniciar guix-daemon; em uma

distribuição que usa systemd como seu gerenciador de serviços, você pode

fazer isso com:

systemctl restart guix-daemon

Depois que a política é instalada, o sistema de arquivos foi rotulado

novamente e o daemon foi reiniciado, ele deve estar em execução no contexto

guix_daemon_t. Você pode confirmar isso com o seguinte comando:

ps -Zax | grep guix-daemon

Monitore os arquivos de log do SELinux enquanto executa um comando como

guix build hello para se convencer de que o SELinux permite todas as

operações necessárias.

2.2.3.2 Limitações

Esta política não é perfeita. Aqui está uma lista de limitações ou peculiaridades que devem ser consideradas ao implementar a política SELinux fornecida para o daemon Guix.

-

guix_daemon_socket_tisn’t actually used. None of the socket operations involve contexts that have anything to do withguix_daemon_socket_t. It doesn’t hurt to have this unused label, but it would be preferable to define socket rules for only this label. -

guix gcnão pode acessar links arbitrários para perfis. Por design, o rótulo do arquivo do destino de uma ligação simbólica é independente do rótulo do arquivo do próprio link. Embora todos os perfis em $localstatedir estejam rotulados, as ligações para esses perfis herdam o rótulo do diretório em que estão. Para as ligações no diretório pessoal do usuário, seráuser_home_t. Mas, para ligações do diretório pessoal do usuário root, ou /tmp, ou do diretório de trabalho do servidor HTTP etc., isso não funcionará.guix gcseria impedido de ler e seguir essas ligações. - O recurso do daemon de escutar conexões TCP pode não funcionar mais. Isso pode exigir regras extras, porque o SELinux trata os soquetes de rede de maneira diferente dos arquivos.

- Atualmente, todos os arquivos com um nome correspondente à expressão regular

/gnu/store/.+-(guix-.+|profile)/bin/guix-daemonrecebem o rótuloguix_daemon_exec_t; isso significa que qualquer arquivo com esse nome em qualquer perfil poderá ser executado no domínio deguix_daemon_t. Isto não é o ideal. Um invasor pode criar um pacote que forneça esse executável e convencer um usuário a instalar e executá-lo, o que o eleva ao domínio deguix_daemon_t. Nesse ponto, o SELinux não poderia impedir o acesso a arquivos permitidos para processos nesse domínio.Você precisará renomear o diretório store após todas as atualizações para guix-daemon, como após executar

guix pull. Supondo que o store esteja em /gnu, você pode fazer isso comrestorecon -vR /gnu, ou por outros meios fornecidos pelo seu sistema operacional.Poderíamos gerar uma política muito mais restritiva no momento da instalação, para que apenas o nome do arquivo exato do executável

guix-daemonatualmente instalado seja rotulado comguix_daemon_exec_t, em vez de usar um amplo expressão regular. A desvantagem é que o root precisaria instalar ou atualizar a política no momento da instalação sempre que o pacote Guix que fornece o executávelguix-daemonem execução efetiva for atualizado.

Próximo: Configuração de aplicativo, Anterior: Configurando o daemon, Acima: Instalação [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.3 Invocando guix-daemon

O programa guix-daemon implementa todas as funcionalidades para

acessar o armazém. Isso inclui iniciar processos de compilação, executar o

coletor de lixo, consultar a disponibilidade de um resultado da compilação

etc. É normalmente executado como root, assim:

# guix-daemon --build-users-group=guixbuild

Este daemon também pode ser iniciado seguindo o protocolo de “ativação de

soquete” do systemd (veja make-systemd-constructor em The GNU Shepherd Manual).

Para detalhes sobre como configurá-lo, veja Configurando o daemon.

Por padrão, guix-daemon inicia processos de compilação sob

diferentes UIDs, obtidos do grupo de compilação especificado com

--build-users-group. Além disso, cada processo de compilação é

executado em um ambiente chroot que contém apenas o subconjunto do armazém

do qual o processo de compilação depende, conforme especificado por sua

derivação (veja derivação), mais um conjunto de

diretórios de sistema específicos. Por padrão, o último contém /dev e

/dev/pts. Além disso, no GNU/Linux, o ambiente de compilação é um

container: além de ter sua própria árvore de sistema de arquivos, ele

tem um espaço de nome de montagem separado, seu próprio espaço de nome PID,

espaço de nome de rede, etc. Isso ajuda a obter compilações reproduzíveis

(veja Recursos).

Quando o daemon executa uma compilação em nome do usuário, ele cria um

diretório de compilação em /tmp ou no diretório especificado por sua

variável de ambiente TMPDIR. Esse diretório é compartilhado com o

contêiner durante a compilação, embora dentro do contêiner, a árvore de

compilação seja sempre chamada de /tmp/guix-build-name.drv-0.

O diretório de compilação é excluído automaticamente após a conclusão, a menos que a compilação falhe e o cliente tenha especificado --keep-failed (veja --keep-failed).

O daemon escuta conexões e gera um subprocesso para cada sessão iniciada por

um cliente (um dos subcomandos guix). O comando guix

processes permite que você tenha uma visão geral da atividade no seu

sistema visualizando cada uma das sessões e clientes ativos. Veja Invocando guix processes, para mais informações.

As seguintes opções de linha de comando são suportadas:

--build-users-group=grupoObtém os usuários do grupo para executar os processos de compilação (veja usuários de compilação).

--no-substitutes¶Não use substitutos para compilar produtos. Ou seja, sempre crie coisas localmente, em vez de permitir downloads de binários pré-compilados (veja Substitutos).

Quando o daemon é executado com --no-substitutes, os clientes ainda podem habilitar explicitamente a substituição por meio da chamada de procedimento remoto

set-build-options(veja O armazém).--substitute-urls=urlsConsider urls the default whitespace-separated list of substitute source URLs. When this option is omitted, ‘

https://bordeaux.guix.gnu.org https://ci.guix.gnu.org’ is used.Isso significa que os substitutos podem ser baixados de urls, desde que assinados por uma assinatura confiável (veja Substitutos).

Veja Obtendo substitutos de outros servidores, para mais informações sobre como configurar o daemon para obter substitutos de outros servidores.

--no-offloadNão use compilações de offload para outras máquinas (veja Usando o recurso de descarregamento). Ou seja, sempre compile as coisas localmente em vez de descarregar compilações para máquinas remotas.

--cache-failuresArmazena em cache as compilações que falharam. Por padrão, apenas compilações bem-sucedidas são armazenadas em cache.

Quando essa opção é usada, o

guix gc --list-failurespode ser usado para consultar o conjunto de itens do armazém marcados como com falha; Oguix gc --clear-failuresremove os itens do armazém do conjunto de falhas em cache. Veja Invocandoguix gc.--cores=n-c nUsa n núcleos de CPU para compilar cada derivação;

0significa todos disponíveis.O valor padrão é

0, mas pode ser substituído pelos clientes, como a opção --cores deguix build(veja Invocandoguix build).O efeito é definir a variável de ambiente

NIX_BUILD_CORESno processo de compilação, que pode então usá-la para explorar o paralelismo interno — por exemplo, executandomake -j$NIX_BUILD_CORES.--max-jobs=n-M nPermite no máximo n tarefas de compilação em paralelo. O valor padrão é

1. Definir como0significa que nenhuma compilação será executada localmente; em vez disso, o daemon descarregará as compilações (veja Usando o recurso de descarregamento) ou simplesmente falhará.--max-silent-time=segundosQuando o processo de compilação ou substituição permanecer em silêncio por mais de segundos, encerra-o e relata uma falha de compilação.

The default value is

3600(one hour).O valor especificado aqui pode ser substituído pelos clientes (veja --max-silent-time).

--timeout=segundosDa mesma forma, quando o processo de compilação ou substituição durar mais que segundos, encerra-o e relata uma falha de compilação.

O valor padrão é 24 horas.

O valor especificado aqui pode ser substituído pelos clientes (veja --timeout).

--rounds=NCompila cada derivação n vezes seguidas e gera um erro se os resultados consecutivos da compilação não forem idênticos bit a bit. Observe que essa configuração pode ser substituída por clientes como

guix build(veja Invocandoguix build).Quando usado em conjunto com --keep-failed, uma saída de comparação é mantida no armazém, sob /gnu/store/…-check. Isso facilita procurar por diferenças entre os dois resultados.

--debugProduz uma saída de depuração.

Isso é útil para depurar problemas de inicialização do daemon, mas pode ser substituído pelos clientes, por exemplo, a opção --verbosity de

guix build(veja Invocandoguix build).--chroot-directory=diradiciona dir ao chroot de compilação.

Isso pode alterar o resultado dos processos de compilação – por exemplo, se eles usam dependências opcionais encontradas em dir quando estão disponíveis, e não o contrário. Por esse motivo, não é recomendável fazê-lo. Em vez disso, verifique se cada derivação declara todas as entradas necessárias.

--disable-chrootDesabilita compilações em chroot.

O uso dessa opção não é recomendado, pois, novamente, isso permitiria que os processos de compilação obtivessem acesso a dependências não declaradas. Porém, é necessário quando o

guix-daemonestá sendo executado em uma conta de usuário sem privilégios.--log-compression=tipoCompacta logs de compilação de aconrdo com tipo, que pode ser um entre

gzip,bzip2enone.A menos que --lose-logs seja usado, todos os logs de build são mantidos em localstatedir. Para economizar espaço, o daemon os compacta automaticamente com gzip por padrão.

--discover[=yes|no]Se deve descobrir servidores substitutos na rede local usando mDNS e DNS-SD.

Este recurso ainda é experimental. No entanto, aqui estão algumas considerações.

- Pode ser mais rápido/menos caro do que buscar em servidores remotos;

- Não há riscos de segurança, apenas substitutos genuínos serão usados (veja Autenticação de substituto);

- Um invasor anunciando

guix publishna sua LAN não pode fornecer binários maliciosos, mas pode descobrir qual software você está instalando; - Os servidores podem servir substitutos via HTTP, sem criptografia, para que qualquer pessoa na LAN possa ver qual software você está instalando.

Também é possível habilitar ou desabilitar a descoberta de servidor substituto em tempo de execução executando:

herd discover guix-daemon on herd discover guix-daemon off

--disable-deduplication¶Desabilita “deduplicação” automática de arquivos no armazém.

Por padrão, os arquivos adicionados ao armazém são automaticamente “deduplicados”: se um arquivo recém-adicionado for idêntico a outro encontrado no armazém, o daemon tornará o novo arquivo um link físico para o outro arquivo. Isso pode reduzir notavelmente o uso do disco, às custas de um leve aumento na carga de entrada/saída no final de um processo de criação. Esta opção desativa essa otimização.

--gc-keep-outputs[=yes|no]Diz se o coletor de lixo (GC) deve manter as saídas de derivações vivas.

Quando definido como

yes, o GC manterá as saídas de qualquer derivação ativa disponível no armazém—os arquivos .drv. O padrão éno, o que significa que as saídas de derivação são mantidas somente se forem acessíveis a partir de uma raiz do GC. Veja Invocandoguix gc, para mais informações sobre raízes do GC.--gc-keep-derivations[=yes|no]Diz se o coletor de lixo (GC) deve manter as derivações correspondentes às saídas vivas.

Quando definido como

yes, como é o caso por padrão, o GC mantém derivações—ou seja, arquivos .drv—desde que pelo menos uma de suas saídas esteja ativa. Isso permite que os usuários acompanhem as origens dos itens em seu armazém. Defini-lo comonoeconomiza um pouco de espaço em disco.Dessa forma, definir --gc-keep-derivations como

yesfaz com que a vivacidade flua das saídas para as derivações, e definir --gc-keep-outputs comoyesfaz com que a vivacidade flua das derivações para as saídas. Quando ambos são definidos comoyes, o efeito é manter todos os pré-requisitos de compilação (as fontes, o compilador, as bibliotecas e outras ferramentas de tempo de compilação) de objetos ativos no armazém, independentemente de esses pré-requisitos serem acessíveis a partir de uma raiz GC. Isso é conveniente para desenvolvedores, pois economiza reconstruções ou downloads.--impersonate-linux-2.6Em sistemas baseados em Linux, personifique o Linux 2.6. Isso significa que a chamada de sistema

unamedo kernel relatará 2.6 como o número da versão.Isso pode ser útil para criar programas que (geralmente de forma errada) dependem do número da versão do kernel.

--lose-logsNão mantenha logs de build. Por padrão, eles são mantidos em localstatedir/guix/log.

--system=sistemaAssuma sistema como o tipo de sistema atual. Por padrão, é o par arquitetura/kernel encontrado no momento da configuração, como

x86_64-linux.--listen=endpointOuça conexões em endpoint. endpoint é interpretado como o nome do arquivo de um soquete de domínio Unix se ele começar com

/(sinal de barra). Caso contrário, endpoint é interpretado como um nome de host ou nome de host e porta para ouvir. Aqui estão alguns exemplos:--listen=/gnu/var/daemonOuça conexões no soquete de domínio Unix /gnu/var/daemon, criando-o se necessário.

--listen=localhost¶-

Ouça as conexões TCP na interface de rede correspondente a

localhost, na porta 44146. --listen=128.0.0.42:1234Ouça as conexões TCP na interface de rede correspondente ao

128.0.0.42, na porta 1234.

Esta opção pode ser repetida várias vezes, nesse caso

guix-daemonaceita conexões em todos os endpoints especificados. Os usuários podem informar aos comandos do cliente a qual endpoint se conectar definindo a variável de ambienteGUIX_DAEMON_SOCKET(vejaGUIX_DAEMON_SOCKET).Nota: O protocolo daemon é unauthenticated and unencrypted. Usar --listen=host é adequado em redes locais, como clusters, onde apenas nós confiáveis podem se conectar ao daemon de compilação. Em outros casos em que o acesso remoto ao daemon é necessário, recomendamos usar soquetes de domínio Unix junto com SSH.

Quando --listen é omitido,

guix-daemonescuta conexões no soquete de domínio Unix localizado em localstatedir/guix/daemon-socket/socket.

Próximo: Atualizando o Guix, Anterior: Invocando guix-daemon, Acima: Instalação [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.4 Configuração de aplicativo

Ao usar Guix sobre uma distribuição GNU/Linux que não seja um Guix System — uma chamada distro alheia — algumas etapas adicionais são necessárias para colocar tudo no seu lugar. Aqui estão algumas delas.

2.4.1 Localidades

Pacotes instalados via Guix não usarão os dados de localidade do sistema

host. Em vez disso, você deve primeiro instalar um dos pacotes de localidade

disponíveis com Guix e então definir a variável de ambiente

GUIX_LOCPATH:

$ guix install glibc-locales $ export GUIX_LOCPATH=$HOME/.guix-profile/lib/locale

Observe que o pacote glibc-locales contém dados para todos os locais

suportados pela GNU libc e pesa cerca de 930 MiB9. Se você precisar apenas

de alguns locais, poderá definir seu pacote de locais personalizados por

meio do procedimento make-glibc-utf8-locales do módulo (gnu

packages base). O exemplo a seguir define um pacote contendo os vários

locais UTF-8 canadenses conhecidos pela GNU libc, que pesa cerca de

14 MiB:

(use-modules (gnu packages base)) (define my-glibc-locales (make-glibc-utf8-locales glibc #:locales (list "en_CA" "fr_CA" "ik_CA" "iu_CA" "shs_CA") #:name "glibc-canadian-utf8-locales"))

A variável GUIX_LOCPATH desempenha um papel similar a LOCPATH

(veja LOCPATH em The GNU C Library Reference

Manual). Há duas diferenças importantes, no entanto:

-

GUIX_LOCPATHé honrado apenas pela libc no Guix, e não pela libc fornecida por distros estrangeiras. Assim, usarGUIX_LOCPATHpermite que você tenha certeza de que os programas da distro estrangeira não acabarão carregando dados de localidade incompatíveis. - libc sufixa cada entrada de

GUIX_LOCPATHcom/X.Y, ondeX.Yé a versão libc—por exemplo,2.22. Isso significa que, caso seu perfil Guix contenha uma mistura de programas vinculados a diferentes versões libc, cada versão libc tentará carregar apenas dados de localidade no formato correto.

Isso é importante porque o formato de dados de localidade usado por diferentes versões da libc pode ser incompatível.

2.4.2 Name Service Switch

Ao usar o Guix em uma distro alheia, nós recomendamos fortemente que

o sistema use o daemon de cache de serviço de nomes da biblioteca C do

GNU, nscd, que deve ouvir no soquete

/var/run/nscd/socket. Caso não faça isso, os aplicativos instalados

com Guix podem falhar em procurar nomes de máquina e contas de usuário, ou

até mesmo travar. Os próximos parágrafos explicam o porquê.

A biblioteca GNU C implementa um name service switch (NSS), que é um mecanismo extensível para “pesquisas de nomes” em geral: resolução de nomes de host, contas de usuários e muito mais (veja Name Service Switch em The GNU C Library Reference Manual).

Sendo extensível, o NSS suporta plugins, que fornecem novas

implementações de pesquisa de nomes: por exemplo, o plugin nss-mdns

permite a resolução de nomes de host .local, o plugin nis

permite a pesquisa de contas de usuários usando o Network information

service (NIS), e assim por diante. Esses "serviços de pesquisa” extras são

configurados em todo o sistema em /etc/nsswitch.conf, e todos os

programas em execução no sistema honram essas configurações (veja NSS

Configuration File em The GNU C Reference Manual).

Quando eles realizam uma pesquisa de nome — por exemplo chamando a função

getaddrinfo em C — os aplicativos primeiro tentam se conectar ao

nscd; em caso de sucesso, o nscd realiza pesquisas de nome em seu nome. Se o

nscd não estiver em execução, eles realizam a pesquisa de nome sozinhos,

carregando os serviços de pesquisa de nome em seu próprio espaço de endereço

e executando-o. Esses serviços de pesquisa de nome — os arquivos

libnss_*.so — são dlopen’d, mas podem vir da biblioteca C do

sistema host, em vez da biblioteca C à qual o aplicativo está vinculado (a

biblioteca C vem do Guix).

E é aqui que está o problema: se seu aplicativo estiver vinculado à

biblioteca C do Guix (por exemplo, glibc 2.24) e tentar carregar plugins NSS

de outra biblioteca C (por exemplo, libnss_mdns.so para glibc 2.22),

ele provavelmente travará ou terá suas pesquisas de nome falhando

inesperadamente.

Executar nscd no sistema, entre outras vantagens, elimina esse

problema de incompatibilidade binária porque esses arquivos

libnss_*.so são carregados no processo nscd, não nos

próprios aplicativos.

Note that nscd is no longer provided on some GNU/Linux distros,

such as Arch Linux (as of Dec. 2024). nsncd can be used as a

drop-in-replacement. See the nsncd

repository and this blog

post for more information.

2.4.3 Fontes X11

A maioria dos aplicativos gráficos usa o Fontconfig para localizar e

carregar fontes e executar renderização do lado do cliente X11. O pacote

fontconfig no Guix procura fontes em $HOME/.guix-profile por

padrão. Assim, para permitir que aplicativos gráficos instalados com o Guix

exibam fontes, você precisa instalar fontes com o Guix também. Pacotes de

fontes essenciais incluem font-ghostscript, font-dejavu e

font-gnu-freefont.

Depois de instalar ou remover fontes, ou quando notar que um aplicativo não encontra fontes, talvez seja necessário instalar o Fontconfig e forçar uma atualização do cache de fontes executando:

guix install fontconfig fc-cache -rv

Para exibir texto escrito em chinês, japonês ou coreano em aplicativos

gráficos, considere instalar font-adobe-source-han-sans ou

font-wqy-zenhei. O primeiro tem várias saídas, uma por família de

idiomas (veja Pacotes com múltiplas saídas). Por exemplo, o comando a

seguir instala fontes para idiomas chineses:

guix install font-adobe-source-han-sans:cn

Programas mais antigos como xterm não usam Fontconfig e, em vez

disso, dependem da renderização de fontes do lado do servidor. Tais

programas exigem a especificação de um nome completo de uma fonte usando

XLFD (X Logical Font Description), como este:

-*-dejavu sans-medium-r-normal-*-*-100-*-*-*-*-*-1

Para poder usar esses nomes completos para as fontes TrueType instaladas no seu perfil Guix, você precisa estender o caminho da fonte do servidor X:

xset +fp $(dirname $(readlink -f ~/.guix-profile/share/fonts/truetype/fonts.dir))

Depois disso, você pode executar xlsfonts (do pacote xlsfonts)

para garantir que suas fontes TrueType estejam listadas lá.

2.4.4 Certificados X.509

O pacote nss-certs fornece certificados X.509, que permitem que

programas autentiquem servidores Web acessados por HTTPS.

Ao usar uma Guix em uma distro alheia, você pode instalar esse pacote e definir as variáveis de ambiente relevantes de forma que os pacotes saibam onde procurar por certificados. Veja Certificados X.509, para informações detalhadas.

2.4.5 Pacotes Emacs

Quando você instala pacotes do Emacs com o Guix, os arquivos Elisp são

colocados no diretório share/emacs/site-lisp/ do perfil no qual eles

são instalados. As bibliotecas Elisp são disponibilizadas para o Emacs por

meio da variável de ambiente EMACSLOADPATH, que é definida ao instalar

o próprio Emacs.

Além disso, as definições de autoload são avaliadas automaticamente na

inicialização do Emacs, pelo procedimento específico do Guix

guix-emacs-autoload-packages. Este procedimento pode ser invocado

interativamente para que pacotes Emacs recém-instalados sejam descobertos,

sem precisar reiniciar o Emacs. Se, por algum motivo, você quiser evitar o

carregamento automático dos pacotes Emacs instalados com o Guix, você pode

fazer isso executando o Emacs com a opção --no-site-file

(veja Init File em The GNU Emacs Manual).

Nota: A maioria das variantes do Emacs agora são capazes de fazer compilação nativa. A abordagem adotada pelo Guix Emacs, no entanto, difere muito da abordagem adotada pelo upstream.

O Upstream Emacs compila pacotes just-in-time e normalmente coloca arquivos de objetos compartilhados em uma pasta especial dentro do seu

user-emacs-directory. Esses objetos compartilhados dentro da referida pasta são organizados em uma hierarquia plana, e seus nomes de arquivo contêm dois hashes para verificar o nome do arquivo original e o conteúdo do código-fonte.O Guix Emacs, por outro lado, prefere compilar pacotes antes do tempo. Objetos compartilhados retêm muito do nome do arquivo original e nenhum hashe é adicionado para verificar o nome do arquivo original ou o conteúdo do arquivo. Crucialmente, isso permite que o Guix Emacs e os pacotes construídos contra ele sejam enxertados (veja enxertos), mas, ao mesmo tempo, o Guix Emacs não tem a verificação baseada em hash do código-fonte embutido no Emacs upstream. Como esse esquema de nomenclatura é trivial de explorar, desabilitamos a compilação just-in-time.

Observe ainda que

emacs-minimal—o Emacs padrão para construir pacotes—foi configurado sem compilação nativa. Para compilar nativamente seus pacotes emacs antes do tempo, use uma transformação como --with-input=emacs-minimal=emacs.

Anterior: Configuração de aplicativo, Acima: Instalação [Conteúdo][Índice]

2.5 Atualizando o Guix

Para atualizar o Guix, execute:

guix pull

Veja Invocando guix pull, para maiores informações.

Em uma distribuição estrangeira, você pode atualizar o daemon de compilação executando:

sudo -i guix pull

seguido por (supondo que sua distribuição use a ferramenta de gerenciamento de serviço systemd):

systemctl restart guix-daemon.service

No sistema Guix, a atualização do daemon é obtida reconfigurando o sistema

(veja guix system reconfigure).

Próximo: Começando, Anterior: Instalação, Acima: GNU Guix [Conteúdo][Índice]

3 Instalação do sistema

Esta seção explica como instalar o Guix System em uma máquina. Guix, como gerenciador de pacotes, também pode ser instalado sobre um sistema GNU/Linux em execução, veja Instalação.

- Limitações

- Considerações de Hardware

- Instalação em um pendrive e em DVD

- Preparando para instalação

- Instalação gráfica guiada

- Instalação manual

- Após a instalação do sistema

- Instalando Guix em uma Máquina Virtual

- Compilando a imagem de instalação

- Construindo a imagem de instalação para placas ARM

Próximo: Considerações de Hardware, Acima: Instalação do sistema [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.1 Limitações

Consideramos que o Guix System está pronto para uma ampla gama de casos de uso de "desktop” e servidores. As garantias de confiabilidade que ele fornece – atualizações e reversões transacionais, reprodutibilidade – tornam-no uma base sólida.

Cada vez mais serviços de sistema são fornecidos (veja Serviços).

No entanto, antes de prosseguir com a instalação, esteja ciente de que alguns serviços dos quais você depende ainda podem estar faltando na versão 4538aa4.

Mais do que um aviso de isenção de responsabilidade, este é um convite para relatar problemas (e histórias de sucesso!) e se juntar a nós para melhorá-los. Veja Contribuindo, para mais informações.

Próximo: Instalação em um pendrive e em DVD, Anterior: Limitações, Acima: Instalação do sistema [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.2 Considerações de Hardware

GNU Guix se concentra em respeitar a liberdade computacional do usuário. Ele é construído em torno do kernel Linux-libre, o que significa que apenas o hardware para o qual existem drivers e firmware de software livre é suportado. Hoje em dia, uma ampla gama de hardware disponível no mercado é suportada no GNU/Linux-libre – de teclados a placas gráficas, scanners e controladores Ethernet. Infelizmente, ainda existem áreas onde os fornecedores de hardware negam aos usuários o controle sobre sua própria computação, e tal hardware não é suportado no Guix System.

Uma das principais áreas onde faltam drivers ou firmware gratuitos são os

dispositivos WiFi. Os dispositivos WiFi que funcionam incluem aqueles que

usam chips Atheros (AR9271 e AR7010), que corresponde ao driver ath9k

Linux-libre, e aqueles que usam chips Broadcom/AirForce (BCM43xx com

Wireless-Core Revisão 5), que corresponde a o driver livre Linux

b43-open. Existe firmware livre para ambos e está disponível

imediatamente no Guix System, como parte do %base-firmware

(veja firmware).

O instalador avisa você antecipadamente se detectar dispositivos que não funcionam devido à falta de firmware ou drivers gratuitos.

A Free Software Foundation administra Respects Your Freedom (RYF), um programa de certificação para produtos de hardware que respeitem sua liberdade e privacidade e garantam que você tenha controle sobre seu dispositivo. Recomendamos que você verifique a lista de dispositivos certificados RYF.

Outro recurso útil é o site H-Node. Ele contém um catálogo de dispositivos de hardware com informações sobre seu suporte no GNU/Linux.

Próximo: Preparando para instalação, Anterior: Considerações de Hardware, Acima: Instalação do sistema [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.3 Instalação em um pendrive e em DVD

Uma imagem de instalação ISO-9660 que pode ser gravada em um pendrive ou

gravada em um DVD pode ser baixada em

‘https://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/guix/guix-system-install-4538aa4.x86_64-linux.iso’,

onde você pode substituir x86_64-linux por um dos seguintes:

x86_64-linuxpara um sistema GNU/Linux em CPUs de 64 bits compatíveis com Intel/AMD;

i686-linuxpara um sistema GNU/Linux de 32 bits em CPUs compatíveis com Intel.

Certifique-se de baixar o arquivo .sig associado e verificar a autenticidade da imagem em relação a ele, seguindo estas linhas:

$ wget https://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/guix/guix-system-install-4538aa4.x86_64-linux.iso.sig $ gpg --verify guix-system-install-4538aa4.x86_64-linux.iso.sig

Se esse comando falhar porque você não possui a chave pública requerida, execute este comando para importá-lo:

$ wget https://sv.gnu.org/people/viewgpg.php?user_id=15145 \

-qO - | gpg --import -

e execute novamente o comando gpg --verify.

Observe que um aviso como "Esta chave não está certificada com uma assinatura confiável!” é normal.

Esta imagem contém as ferramentas necessárias para uma instalação. Ele deve ser copiado como está para um pendrive ou DVD grande o suficiente.

Copiando para um pendrive

Insira um pendrive de 1 GiB ou mais em sua máquina e determine o nome do dispositivo. Supondo que o pendrive seja conhecido como /dev/sdX, copie a imagem com:

dd if=guix-system-install-4538aa4.x86_64-linux.iso of=/dev/sdX status=progress sync

O acesso a /dev/sdX geralmente requer privilégios de root.

Gravando em um DVD

Insira um DVD virgem em sua máquina e determine o nome do dispositivo. Supondo que a unidade de DVD seja conhecida como /dev/srX, copie a imagem com:

growisofs -dvd-compat -Z /dev/srX=guix-system-install-4538aa4.x86_64-linux.iso

O acesso a /dev/srX geralmente requer privilégios de root.

Inicializando

Feito isso, você poderá reiniciar o sistema e inicializar a partir do

pendrive ou DVD. O último geralmente requer que você entre no menu de

inicialização do BIOS ou UEFI, onde você pode optar por inicializar a partir

do pendrive. Para inicializar a partir do Libreboot, mude para o modo de

comando pressionando a tecla c e digite search_grub usb.

Infelizmente, em algumas máquinas, o meio de instalação não pode ser inicializado corretamente e você só verá uma tela preta após a inicialização, mesmo depois de esperar dez minutos. Isto pode indicar que sua máquina não consegue executar o Sistema Guix; talvez você queira instalar o Guix em uma distribuição estrangeira (veja Instalação de binários). Mas não desista ainda; uma possível solução alternativa é pressionar a tecla e no menu de inicialização do GRUB e anexar nomodeset à linha de inicialização do Linux. Às vezes, o problema da tela preta também pode ser resolvido conectando um monitor diferente.

Veja Instalando Guix em uma Máquina Virtual, se, em vez disso, você quiser instalar o Guix System em uma máquina virtual (VM).

Próximo: Instalação gráfica guiada, Anterior: Instalação em um pendrive e em DVD, Acima: Instalação do sistema [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.4 Preparando para instalação

Depois de inicializar, você pode usar o instalador gráfico guiado, o que facilita o início (veja Instalação gráfica guiada). Alternativamente, se você já está familiarizado com GNU/Linux e deseja mais controle do que o instalador gráfico oferece, você pode escolher o processo de instalação "manual” (veja Instalação manual).

O instalador gráfico está disponível em TTY1. Você pode obter shells root em TTYs 3 a 6 pressionando ctrl-alt-f3, ctrl-alt-f4, etc. TTY2 mostra esta documentação e você pode acessá-la com ctrl-alt -f2. A documentação pode ser navegada usando os comandos do leitor de informações (veja Stand-alone GNU Info). O sistema de instalação executa o daemon do mouse GPM, que permite selecionar texto com o botão esquerdo do mouse e colá-lo com o botão do meio.

Nota: A instalação requer acesso à Internet para que quaisquer dependências ausentes na configuração do sistema possam ser baixadas. Consulte a seção "Rede" abaixo.

Próximo: Instalação manual, Anterior: Preparando para instalação, Acima: Instalação do sistema [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.5 Instalação gráfica guiada

O instalador gráfico é uma interface de usuário baseada em texto. Ele guiará você, com caixas de diálogo, pelas etapas necessárias para instalar o GNU Guix System.

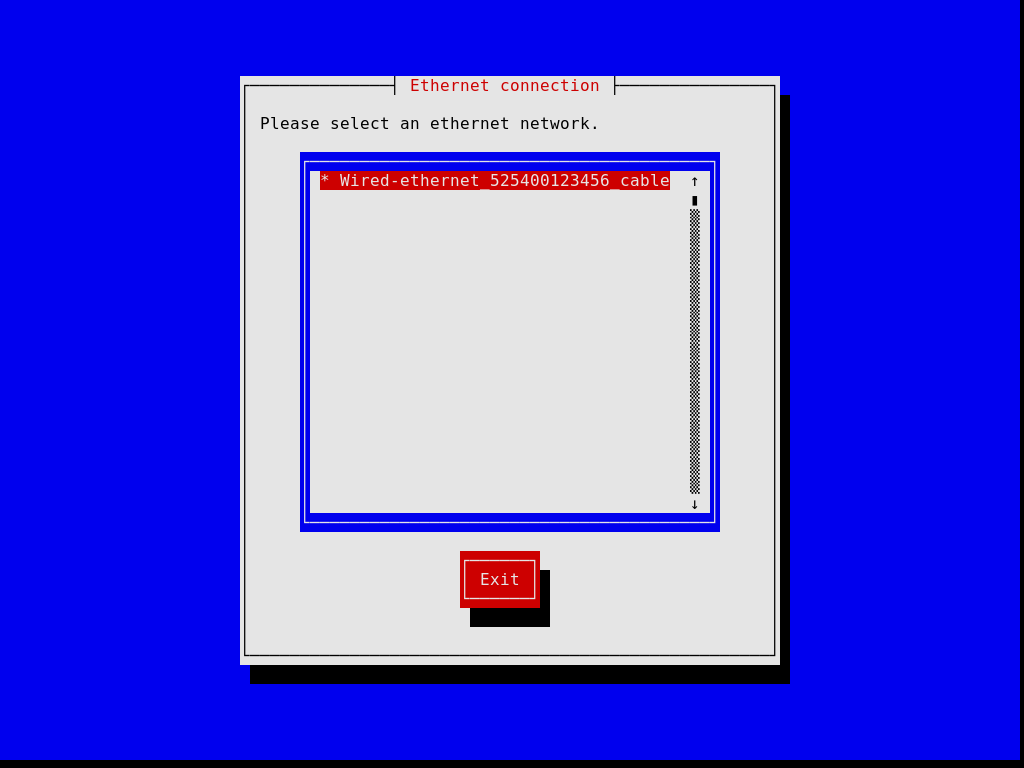

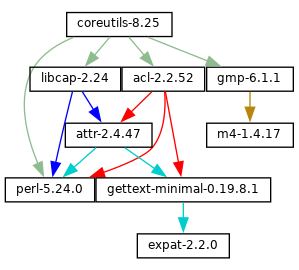

As primeiras caixas de diálogo permitem que você configure o sistema conforme você o utiliza durante a instalação: você pode escolher o idioma, o layout do teclado e configurar a rede que será usada durante a instalação. A imagem abaixo mostra a caixa de diálogo de rede.

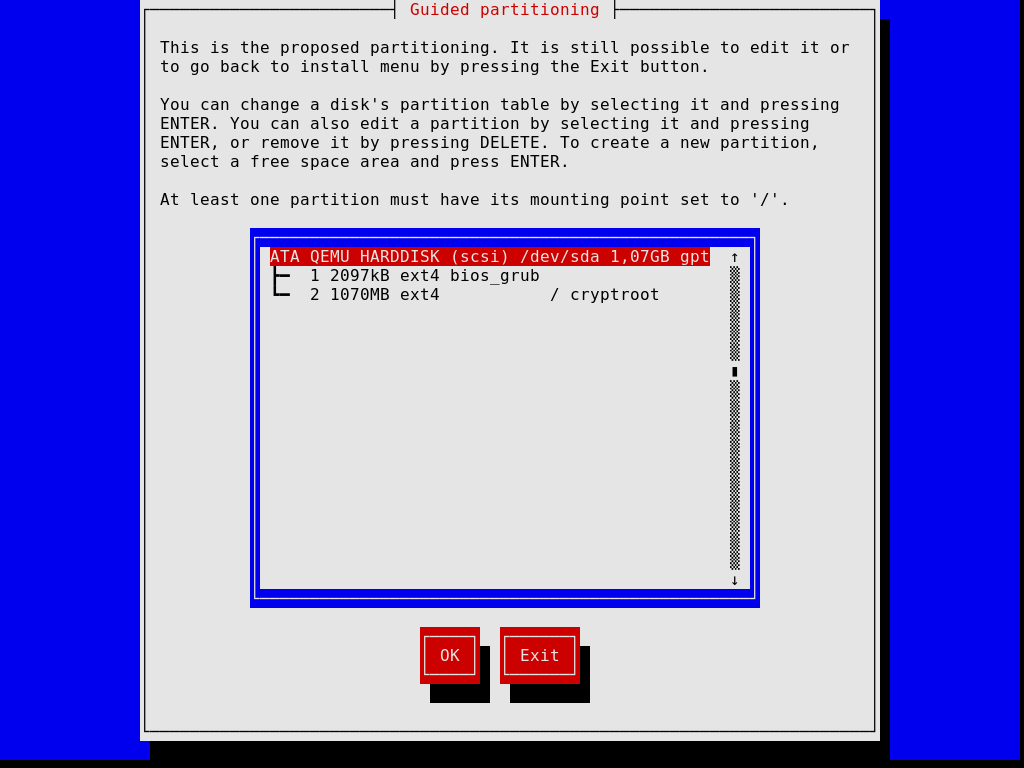

As etapas posteriores permitem particionar seu disco rígido, conforme mostrado na imagem abaixo, escolher se deseja ou não usar sistemas de arquivos criptografados, inserir o nome do host e a senha root e criar uma conta adicional, entre outras coisas.

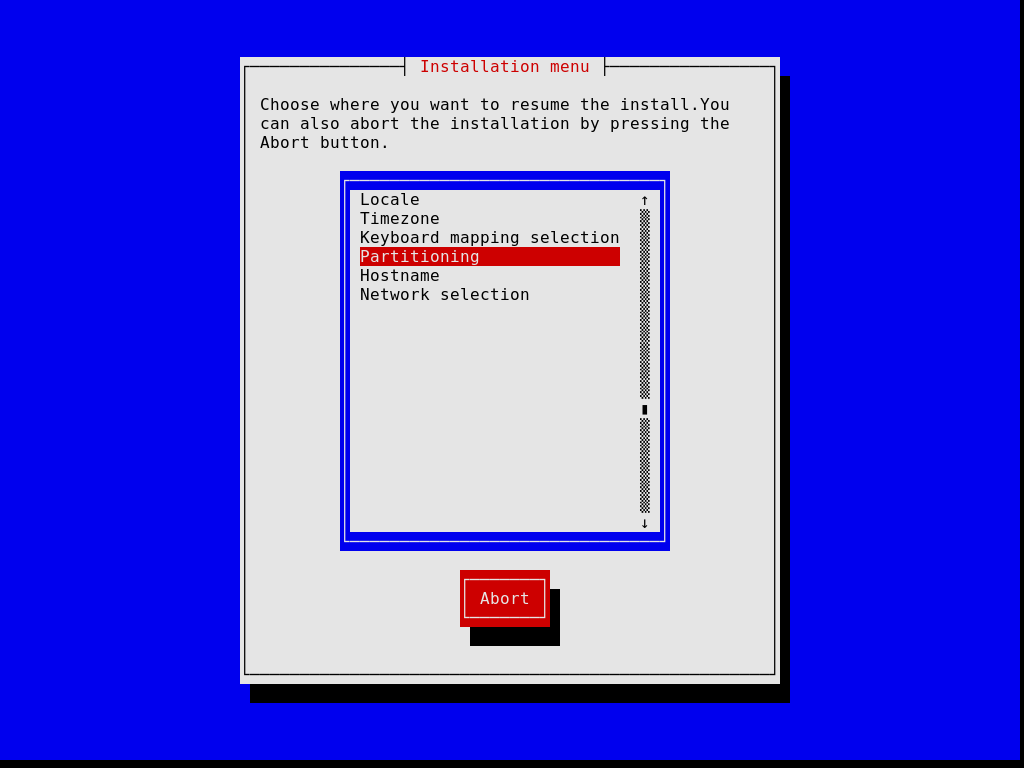

Observe que, a qualquer momento, o instalador permite sair da etapa de instalação atual e retomar uma etapa anterior, conforme imagem abaixo.

Quando terminar, o instalador produz uma configuração do sistema operacional e a exibe (veja Usando o sistema de configuração). Nesse ponto você pode clicar em "OK” e a instalação continuará. Se tiver sucesso, você pode reiniciar no novo sistema e aproveitar. Veja Após a instalação do sistema, para saber o que vem a seguir!

Próximo: Após a instalação do sistema, Anterior: Instalação gráfica guiada, Acima: Instalação do sistema [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.6 Instalação manual

Esta seção descreve como você instalaria "manualmente” o GNU Guix System em sua máquina. Esta opção requer familiaridade com GNU/Linux, com o shell e com ferramentas de administração comuns. Se você acha que isso não é para você, considere usar o instalador gráfico guiado (veja Instalação gráfica guiada).

O sistema de instalação fornece shells root nos TTYs 3 a 6; pressione

ctrl-alt-f3, ctrl-alt-f4 e assim por diante para

alcançá-los. Inclui muitas ferramentas comuns necessárias para instalar o

sistema, mas também é um sistema Guix completo. Isso significa que você pode

instalar pacotes adicionais, caso precise, usando guix package

(veja Invocando guix package).

Próximo: Prosseguindo com a instalação, Acima: Instalação manual [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.6.1 Layout de teclado, rede e particionamento

Antes de instalar o sistema, você pode querer ajustar o layout do teclado, configurar a rede e particionar o disco rígido de destino. Esta seção irá guiá-lo através disso.

3.6.1.1 Disposição do teclado

A imagem de instalação usa o layout de teclado qwerty dos EUA. Se quiser

alterá-lo, você pode usar o comando loadkeys. Por exemplo, o

comando a seguir seleciona o layout do teclado Dvorak:

loadkeys dvorak

Consulte os arquivos em /run/current-system/profile/share/keymaps

para obter uma lista de layouts de teclado disponíveis. Execute man

loadkeys para obter mais informações.

3.6.1.2 Rede

Execute o seguinte comando para ver como são chamadas suas interfaces de rede:

ifconfig -a

… ou, usando o comando ip específico do GNU/Linux:

ip address

As interfaces com fio têm um nome que começa com ‘e’; por exemplo, a interface correspondente ao primeiro controlador Ethernet integrado é chamada ‘eno1’. As interfaces sem fio têm um nome que começa com ‘w’, como ‘w1p2s0’.

- Conexão cabeada

Para configurar uma rede com fio execute o seguinte comando, substituindo interface pelo nome da interface com fio que você deseja usar.

ifconfig interface up

… ou, usando o comando

ipespecífico do GNU/Linux:ip link set interface up

- Conexão sem fio ¶

-

Para configurar a rede sem fio, você pode criar um arquivo de configuração para a ferramenta de configuração

wpa_supplicant(sua localização não é importante) usando um dos editores de texto disponíveis, comonano:nano wpa_supplicant.conf

Como exemplo, a sub-rotina a seguir pode ir para este arquivo e funcionará para muitas redes sem fio, desde que você forneça o SSID e a senha reais da rede à qual está se conectando:

network={ ssid="my-ssid" key_mgmt=WPA-PSK psk="the network's secret passphrase" }Inicie o serviço sem fio e execute-o em segundo plano com o seguinte comando (substitua interface pelo nome da interface de rede que deseja usar):

wpa_supplicant -c wpa_supplicant.conf -i interface -B

Execute

man wpa_supplicantpara obter mais informações.

Neste ponto, você precisa adquirir um endereço IP. Em uma rede onde os endereços IP são atribuídos automaticamente via DHCP, você pode executar:

dhclient -v interface

Tente executar ping em um servidor para ver se a rede está funcionando:

ping -c 3 gnu.org

Configurar o acesso à rede é quase sempre um requisito porque a imagem não contém todos os softwares e ferramentas que podem ser necessários.

Se você precisar de acesso HTTP e HTTPS para passar por um proxy, execute o seguinte comando:

herd set-http-proxy guix-daemon URL

onde URL é a URL do proxy, por exemplo http://example.org:8118.

Se desejar, você pode continuar a instalação remotamente iniciando um servidor SSH:

herd start ssh-daemon

Certifique-se de definir uma senha com passwd ou configurar a

autenticação de chave pública OpenSSH antes de efetuar login.

3.6.1.3 Particionamento de disco

A menos que isso já tenha sido feito, o próximo passo é particionar e então formatar a(s) partição(ões) de destino.

A imagem de instalação inclui várias ferramentas de particionamento,

incluindo Parted (veja Overview em GNU Parted User Manual),

fdisk e cfdisk. Execute-a e configure seu disco com o

layout de partição que você deseja:

cfdisk

Se o seu disco usa o formato GUID Partition Table (GPT) e você planeja instalar o GRUB baseado em BIOS (que é o padrão), certifique-se de que uma partição de inicialização do BIOS esteja disponível (veja BIOS installation em manual do GNU GRUB).

Se você preferir usar o GRUB baseado em EFI, uma partição de sistema EFI

(ESP) FAT32 EFI System Partition é necessária. Essa partição pode ser

montada em /boot/efi, por exemplo, e deve ter o sinalizador

esp definido. Por exemplo, para parted:

parted /dev/sda set 1 esp on

Nota: Não tem certeza se deve usar o GRUB baseado em EFI ou BIOS? Se o diretório /sys/firmware/efi existir na imagem de instalação, então você provavelmente deve executar uma instalação EFI, usando

grub-efi-bootloader. Caso contrário, você deve usar o GRUB baseado em BIOS, conhecido comogrub-bootloader. Veja Configuração do carregador de inicialização, para mais informações sobre bootloaders.

Depois de terminar de particionar o disco rígido de destino, você precisa criar um sistema de arquivos na(s) partição(ões) relevante(s)10. Para o ESP, se você tiver um e presumindo que seja /dev/sda1, execute:

mkfs.fat -F32 /dev/sda1

Para o sistema de arquivos raiz, ext4 é o formato mais amplamente usado. Outros sistemas de arquivos, como Btrfs, suportam compressão, que é relatada como um bom complemento para a desduplicação de arquivos que o daemon executa independentemente do sistema de arquivos (veja deduplication).

De preferência, atribua um rótulo aos sistemas de arquivos para que você

possa se referir a eles de forma fácil e confiável nas declarações

file-system (veja Sistemas de arquivos). Isso normalmente é feito usando a

opção -L de mkfs.ext4 e comandos relacionados. Então,

assumindo que a partição raiz de destino esteja em /dev/sda2, um

sistema de arquivos com o rótulo my-root pode ser criado com:

mkfs.ext4 -L my-root /dev/sda2

Se você estiver planejando criptografar a partição raiz, você pode usar os

utilitários Cryptsetup/LUKS para fazer isso (veja man cryptsetup para mais informações).

Supondo que você queira armazenar a partição raiz em /dev/sda2, a sequência de comandos para formatá-la como uma partição LUKS seria algo como isto:

cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/sda2 cryptsetup open /dev/sda2 my-partition mkfs.ext4 -L my-root /dev/mapper/my-partition

Feito isso, monte o sistema de arquivos de destino em /mnt com um

comando como (novamente, assumindo que my-root é o rótulo do sistema

de arquivos raiz):

mount LABEL=my-root /mnt

Monte também quaisquer outros sistemas de arquivos que você gostaria de usar

no sistema de destino em relação a este caminho. Se você optou por

/boot/efi como um ponto de montagem EFI, por exemplo, monte-o em

/mnt/boot/efi agora para que ele seja encontrado por guix

system init depois.

Por fim, se você planeja usar uma ou mais partições swap (veja Espaço de troca (swap)), certifique-se de inicializá-las com mkswap. Supondo que

você tenha uma partição swap em /dev/sda3, você executaria:

mkswap /dev/sda3 swapon /dev/sda3

Alternativamente, você pode usar um arquivo de swap. Por exemplo, supondo que no novo sistema você queira usar o arquivo /swapfile como um arquivo de swap, você executaria 11:

# Este é 10 GiB de espaço de swap. Ajuste "count" para alterar o tamanho. dd if=/dev/zero of=/mnt/swapfile bs=1MiB count=10240 # Por segurança, torne o arquivo legível e gravável somente pelo root. chmod 600 /mnt/swapfile mkswap /mnt/swapfile swapon /mnt/swapfile

Observe que se você criptografou a partição raiz e criou um arquivo de swap em seu sistema de arquivos, conforme descrito acima, a criptografia também protegerá o arquivo de swap, assim como qualquer outro arquivo naquele sistema de arquivos.

Anterior: Layout de teclado, rede e particionamento, Acima: Instalação manual [Conteúdo][Índice]

3.6.2 Prosseguindo com a instalação

Com as partições de destino prontas e a raiz de destino montada em /mnt, estamos prontos para começar. Primeiro, execute:

herd start cow-store /mnt

Isso torna /gnu/store copy-on-write, de modo que os pacotes

adicionados a ele durante a fase de instalação são gravados no disco de

destino em /mnt em vez de mantidos na memória. Isso é necessário

porque a primeira fase do comando guix system init (veja abaixo)

envolve downloads ou compilações para /gnu/store que, inicialmente, é

um sistema de arquivos na memória.

Em seguida, você precisa editar um arquivo e fornecer a declaração do

sistema operacional a ser instalado. Para isso, o sistema de instalação vem