Reinstating an iconic error message

Software development is a social process. What might be a “bug” for someone might well be a “feature” for someone else. The Guix project rediscovered it the hard way when, after “fixing a bug” that had been present in Guix System for years, it was confronted with an uproar in its user base.

In this post we look at why developers considered the initial behavior a “bug”, why users on the contrary had come to rely on it, and why developers remained blind to it. A patch to reinstate the initial behavior is being reviewed. This post is also an opportunity for us Guix developers to extend our apologies to our users whose workflow was disrupted.

The crux of the matter

Anyone who’s used Guix System in the past has seen this message on the console during the boot process:

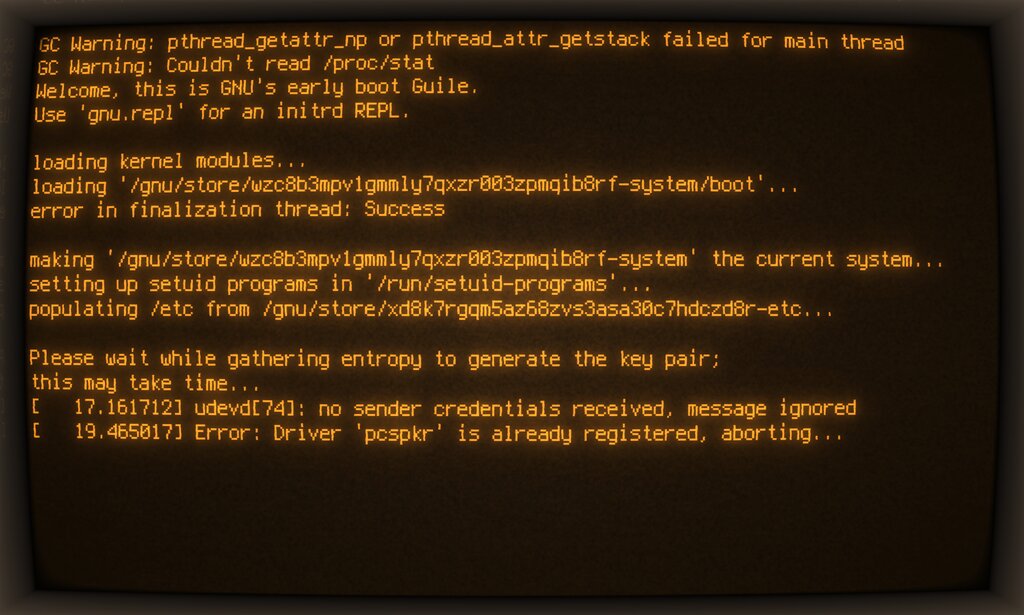

error in finalization thread: SuccessThe following picture shows a typical boot screen (with additional messages in the same vein):

If you have never seen it before, it may look surprising to you. Guix System users lived with it literally for years; the message became a hint that the boot process was, indeed, successful.

A few months ago, a contributor sought to satisfy their curiosity by finding the origin of the message. It did look like a spurious error message, after all, and perhaps the right course of action would be to address the problem at its root—or so they thought.

As it turns out, the message originated in

Guile—check

out the Guile

manual

if you’re curious about finalization. Investigation revealed two

things: first, that this perror call in Guile was presumably reporting

the wrong error code—this was

fixed.

The second error—the core of the problem—lied in Guix System itself.

Remember that, in its quest of memory safety™, statelessness, and fun,

Guix System does it all in Guile Scheme—well, except for the kernel (for

now). As soon as Linux has booted, Guix System spawns Guile to run boot

code that’s in its initial RAM

disk

(“initrd”). Right before executing

shepherd, its service manager, as

PID 1, the initrd code would carelessly close all the file descriptors

above 2 to make sure they do not leak into PID 1. The problem—you

guessed it—is that one of them was the now-famous file descriptor of the

finalization thread’s pipe; the finalization thread would quickly notice

and boom!

error in finalization thread: SuccessOur intrepid developers thought: “hey, we found it! Let’s fix it!”. And so they did.

Breaking user workflows

This could have been the end of the story, but there’s more to it than software. As Xkcd famously captured, this was bound to break someone’s workflow. Indeed, had developers paid more attention to what users had to say, they would have known that the status quo was preferable.

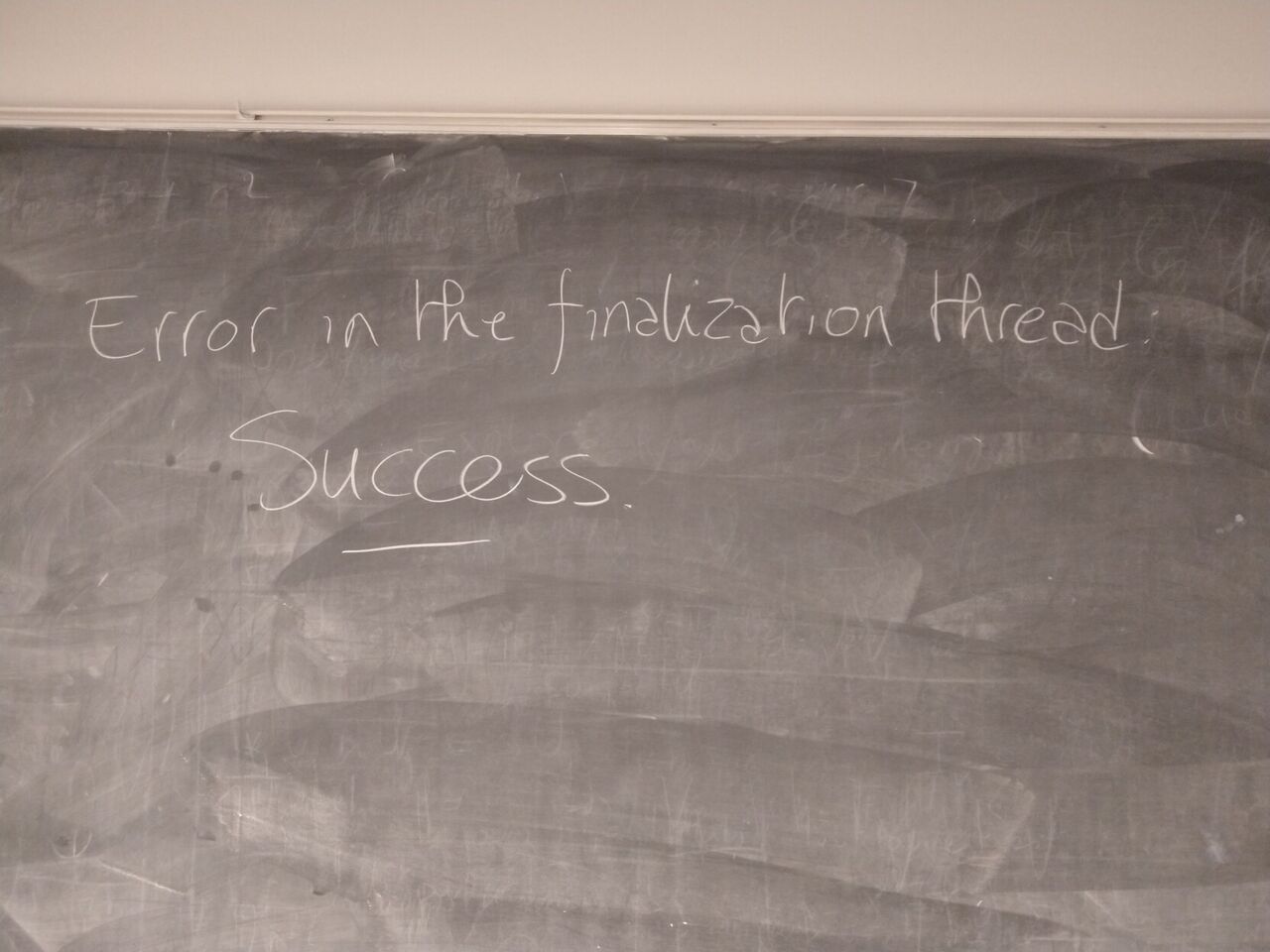

For some time now, users had shown that they held the error/success message deep in their heart. The message was seen on the blackboard at the Ten Years of Guix celebration, as a motto, as a rallying cry, spontaneously put on display:

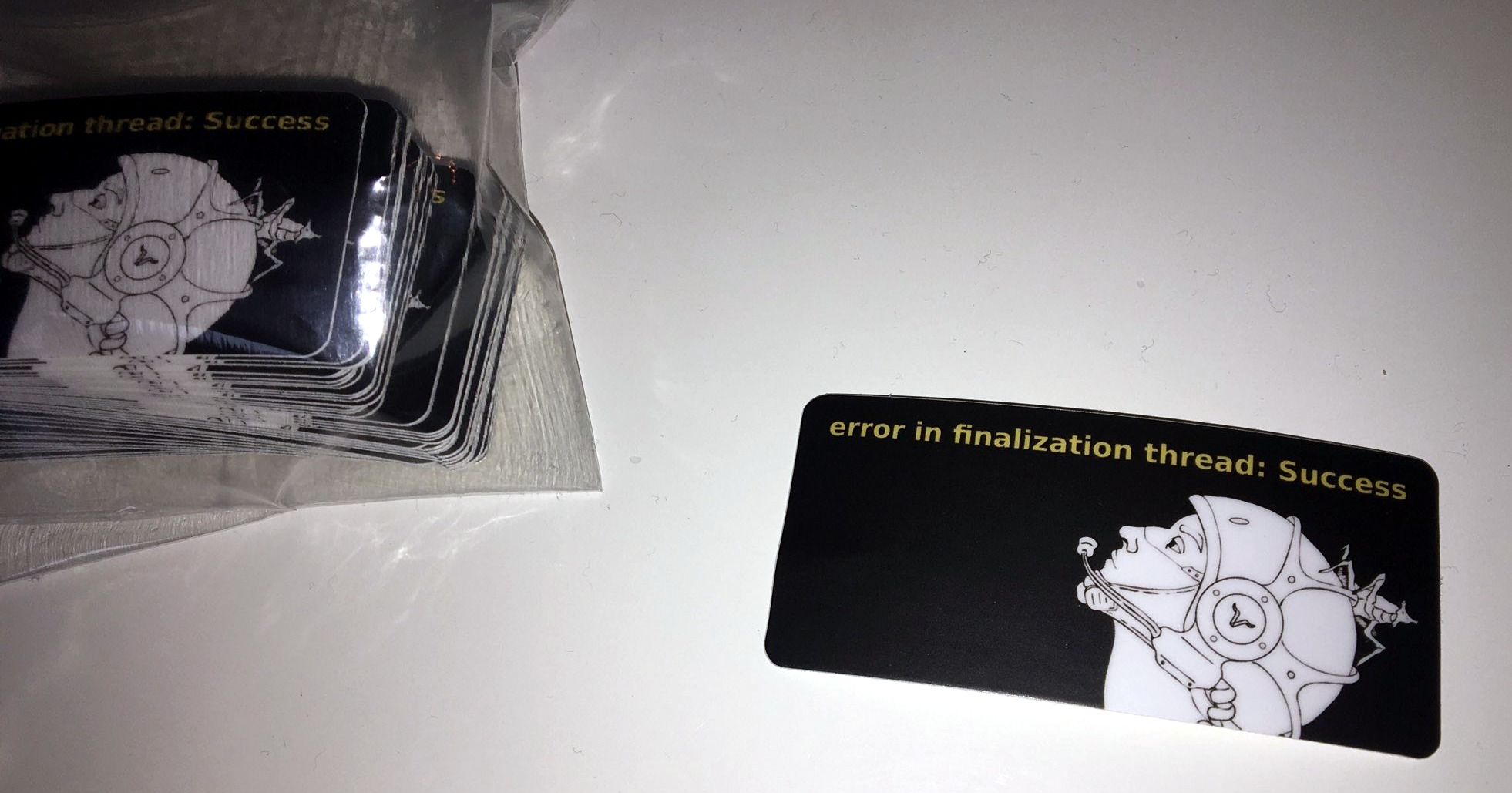

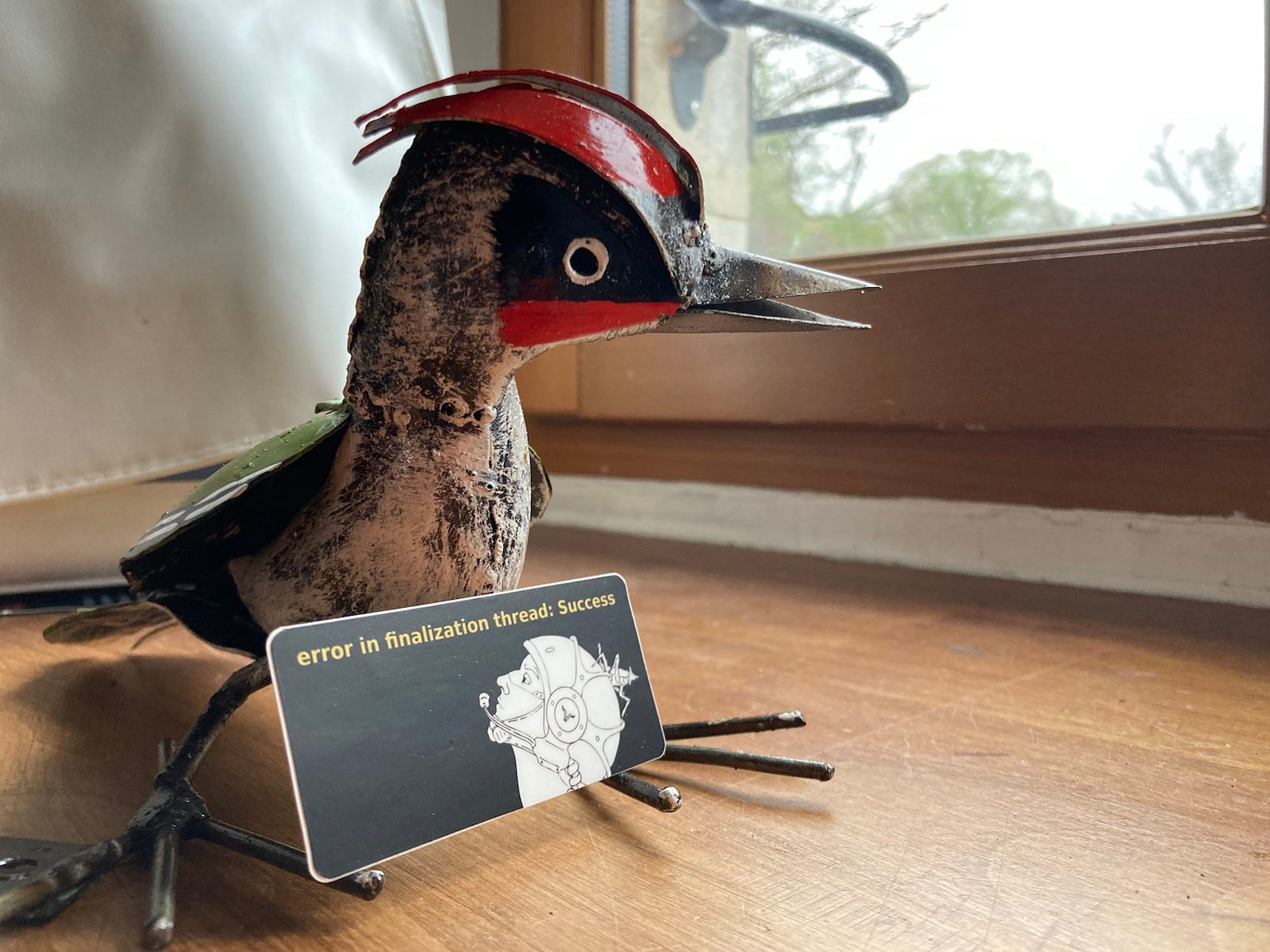

What’s more, a fellow NixOS hacker and Guix enthusiast, beguiled by this powerful message, designed stickers and brought them to FOSDEM in February 2023:

The sticker design builds upon the “test pilot” graphics made by Luis Felipe for the 1.3.0 release. The test pilot has a bug on its helmet. In a way, the drawing and error message both represent, metaphorically, a core tenet of Guix as a project; just like Haskell is avoiding success at all costs, Guix seems trapped in an error/success quantum state.

Had it gone too far? Was calling it a “bug” the demonstration of the arrogance of developers detached from the reality of the community?

Fixing our mistakes

Those who installed Guix System starting from version

1.4.0 have

been missing out on the error/success boot message. The patch

submitted today finally reinstates

that message. The review process will determine whether consensus is to

enable it by default—as part of

%base-service—or

whether to make it optional—after all, we also need to accommodate the

needs of new users who never saw this message. This will allow users

to restore their workflow, while also ensuring that those freshly

printed stickers remain relevant.

This incident had broader consequences in the project. It led some to suggest that we, finally, set up a request-for-comment (RFC) kind of process that would give all the community a say on important topics—a process most large free software projects have developed in one form or another. Such a process could have prevented this incident: instead of arrogantly labeling it as a “bug”, developers would have proposed an RFC to remove the message; the discussion period, most likely, would have made it clear that removal was not a desirable outcome and we would all have moved on.

This incident made many users uncomfortable, but we are glad that it is now being addressed. The lessons learned will be beneficial to the project for the years to come.

Credits

Test pilot by Luis Felipe distributed under the terms of CC-BY-SA 4.0; sticker design distributed under CC-BY-SA 4.0 as well. Blackboard picture by Julien Lepiller under CC0; sticker pictures under CC0.

Many thanks to the anonymous sticker provider!

About GNU Guix

GNU Guix is a transactional package manager and an advanced distribution of the GNU system that respects user freedom. Guix can be used on top of any system running the Hurd or the Linux kernel, or it can be used as a standalone operating system distribution for i686, x86_64, ARMv7, AArch64 and POWER9 machines.

In addition to standard package management features, Guix supports transactional upgrades and roll-backs, unprivileged package management, per-user profiles, and garbage collection. When used as a standalone GNU/Linux distribution, Guix offers a declarative, stateless approach to operating system configuration management. Guix is highly customizable and hackable through Guile programming interfaces and extensions to the Scheme language.

Wenn nicht anders angegeben, sind Blogeinträge auf diesem Webauftritt urheberrechtlich geschützt zugunsten ihrer jeweiligen Verfasser und veröffentlicht zu den Bedingungen der Lizenz CC-BY-SA 4.0 und der GNU Free Documentation License (Version 1.3 der Lizenz oder einer späteren Version, ohne unveränderliche Abschnitte, ohne vorderen Umschlagtext und ohne hinteren Umschlagtext).